“Margarida was extremely thin, with enormous eyes, like a bird that never comes to earth. She spoke very little but she created an almost suffocating magnetic field around herself. Antonio spoke a lot, but suddenly Margarida would snatch him up in the air, take him outside and people stopped hearing them. What did they talk about there, among the clouds, or in the bowels of the earth? Perhaps they talked about films to be made, screams of terror were heard, muffled by the clouds, bloodied feathers fell, splashes of red darkened the tone of the water. When they came back, more composed and serene, dressed as people, they pretended again to be a couple like other couples, a couple of artists… We’ll never know what moved them. Love? War? Blood? Fear? Challenges? Next to them, the works of love by other couples lost their spark, lost their fire. Poor us. Who could imitate them?”

This was the image that the filmmaker Paulo Rocha kept of his colleagues Margarida Cordeiro (1939) and António Reis (1927-1991), the violent and tender, discreet and scandalous —as Rocha remembered them— protagonists of that extraordinary moment in Portuguese cinema that goes from the mid-60s to the mid-80s and that, with intervals, capitulations and flashes, continues today, with the result that some of the films that still come from that place continue to figure among the most vital and inquisitive in the world. But where did that pair of solidary, solitary phoenix come from, those two figures, impetuous and surly but, according to the memory of those who mixed with them, also “magnetic”, “inimitable”?

Less known than Manoel de Oliveira, Pedro Costa or Paulo Rocha, their work is as decisive as that of any of them, and João Bénard da Costa even said that their cinema was “one of the great acts of love and creation that Portuguese art has given us (…), one of the few road markers that can help us find our way again.” That way should be first sought in an earlier episode, in that matrixlike film for Portuguese cinema, Rite of Spring (Manoel de Oliveira, 1963) because that was where Rocha and Reis met as assistant directors to Oliveira (although Reis’s role, as we will see, was far from limited to that of a simple observer).

Rite of Spring was Oliveira’s return to cinema, his first feature film after twenty one years of enforced silence. With it he took up again the avant garde gesture of his first films while anticipating the future ones. The film connects with the best of the new cinemas of the ‘60s through one of its least obvious streams: the anthropological root that places Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960) in I, a Negro (Jean Rouch, 1958), L'Amour fou (Jacques Rivette, 1969) in The Mad Masters (Rouch, 1955), Black God, White Devil (Glauber Rocha, 1964) in the documentaries by Humberto Mauro. Rite of Spring accompanies or heralds all that and shows Oliveira’s skill in positioning himself, despite the years of inactivity, at the centre of the great current of renovation of cinema at the time. But the film also has a much more discreet origin that should be sought precisely in the figure of António Reis.

As a member of the Porto film club, Reis had inspired the shooting of a modest but very beautiful collective amateur film, on 8mm, titled O auto da Floripes (1959-1963). If Oliveira’s film gave cinematic shape to a religious theatrical representation that was held each year in the village of Curalha in Tràs-Os-Montes, O auto da Floripes showed the same kind of representation (although profane) in another village in the same region. It was after seeing O auto da Floripes that Oliveira suggested to Reis that he help him make Rite of Spring. And one could almost talk of a remake, as both films share the same structure: the theatrical works are preceded by a long introduction in which we see the townspeople, who will later play roles in the representation, going about their daily work. However Oliveira would look for the way to take the amateur film’s discovery ever farther, with that radical criticism of the conventions of representation that his film displays.

But if anything distances Rite of Spring from its primitive model it is the stylized, musical treatment that Oliveira gives to the word. A question to which Reis was particularly sensitive, as he showed in an interview in which he criticized the Portuguese that was spoken in the film for not being the Portuguese of Trás-os-Montes, and pointed out the paradox which the actors faced: “It’s like the transformation suffered by an erudite painting at the hands of a popular painter “.

Reflections like this would serve Reis when three years later Paulo Roche commissioned him to write the dialogue in his film Change One’s Life (1966). Rocha’s second feature film is set in a fishing community in the north, and if the film doesn’t completely turn its back on its documentary undertone it’s thanks to the precision of dialogue that manages to transcend the hindrance of dubbing.

They were places and people that Reis knew very well, and not so much because he’d been born near there and his humble origins meant that he’d grown up surrounded by fishermen and labourers like those who appear in the film, but because at a later moment he had gone back to those places, interested in their ways of life and popular arts.

Reis was known in Porto’s artistic circles as a poet, but also as an amateur folklorist. Speaking of the field studies he made at that time, he said: “I suffer at and am dazzled by large and small things, which perhaps are considered of no interest from an ethnographic point of view. I think, for example, of a fire that I saw them make by tying a dried acorn to a piece of glass, and then rubbing with a flint stone stuck in a block of wood; or of the embers that a woman asked for in the town bakery in order to put in her clothes iron; or of the trays of little mackerel that the same woman grilled, as a favor, in the bread oven.” Observations like these, far removed from any orthodoxy but attentive to sensorial and deeply symbolic aspects of the intimacy of the people and their land, will become a basic material in the films by Reis and Cordeiro.

The dialogue in Change One’s Life —dry, harsh, staccato... just the opposite of those in Rite of Spring, this mini-season is an opportunity to compare them— was well received by Rocha, who encouraged Reis to keep trying his luck in the world of professional cinema, in Lisbon. There he tried to set up his first projects and he started teaching a course (“Filmic space”) in the Escola Superior de Cinema e Teatro, where he left his mark on generations of future filmmakers for his “seriousness”, “self-discipline” and “vast culture”, as his former student Pedro Costa recalled.

Costa is probably the filmmaker who best assimilated not only Reis’s formal lessons but something more decisive: his attitude to life and work. But the interesting thing isn’t to ask what Costa learned from Reis, but just the opposite: to what extent Costa’s films throw light on angles still little known of the films by Reis and Cordeiro. Films like Blood, In Vanda’s Room or Horse Money, teach us to see certain shots by Cordeiro and Reis, creating continuities regarding which, if you can speak of influence, it would have to be done in the opposite direction.

And the same can be said of other recent Portuguese films, such as Barbs, Wastelands, which show to what extent the work by Cordeiro and Reis has defined some useful coordinates for the work by filmmakers who have come afterwards. The film by Marta Mateus widens this context, referring to an episode that is implicit in the feature films by Cordeiro and Reis: the Agrarian Reform of 1976, which for a brief period of time recognized the historic struggles by the Portuguese peasants. It does this through the summer itinerary of some children who discover that story through their grandparents. The generation gap, unemployment in a region, and the loss of their ways of work and of life, the scars of the struggles, are subjects we will also find in the films by Reis and Cordeiro.

The journey to Lisbon was also important because that was where Reis met Margarida Cordeiro, who would become his permanent associate and co-director of future films. Cordeiro was working as a psychiatrist in the Miguel Bombarda Hospital in that city, and it was she who spoke to Reis of the moving drawings which a resident, Jaime Fernandes, had left on his death. The couple started to work on what would end up being their first film: a tribute to Jaime’s blurred figure.

If in general it’s difficult to describe any film by Cordeiro and Reis from the point of view of its genre (“pre-socratic”, Jacques Rivette called them, and perhaps that is the most precise thing that can be said about them,) it is even more so in the case of Jaime (1974), one of the most “unexpected”» films that exist —the adjective is now from João César Monteiro, who also considered it one of the best in the history of cinema. For that reason, perhaps rather than asking what Jaime is, it could be useful to start by trying to think who Jaime was. And that is where the film’s title gives us a fundamental clue: Jaime is Jaime, an ordinary name like that of the multitude of ordinary Portuguese at whom the film was aimed. This was what the film tried to show and that was, undoubtedly, the most scandalous thing. Reis and Cordeiro had known to avoid all the traps —many and compatible between themselves— that would have presented Jaime as abnormality, that is: as someone sick and not as someone who had been locked up for thirty eight years; as an outsider and not as a pauper; as a brut artist and not as a peasant.

The film was shot in the run-up to the 25th April revolution, but it opened just a week after that date, and the feature film that was programmed along with it seemed the most suitable: Battleship Potemkin, banned in Portugal for forty two years. Margarida Cordeiro recalled how honoured António Reis always felt about that circumstance.

Knowledge of the period following 25th April and of the films that were made about that date is necessary in order to understand fully the three feature films by Cordeiro and Reis. They form part of that time and that movement, but they also move forcefully away from what cinema and Portuguese politics were then. The fundamental gesture consisted of abandoning the roar of the capital to go and film in the poorest, most forgotten region in the country, Trás-os-Montes, where they would now film all their work. “Also the shadow of a tree was, is, aesthetically geopolitical, participant and revolutionary”, Reis said at that time.

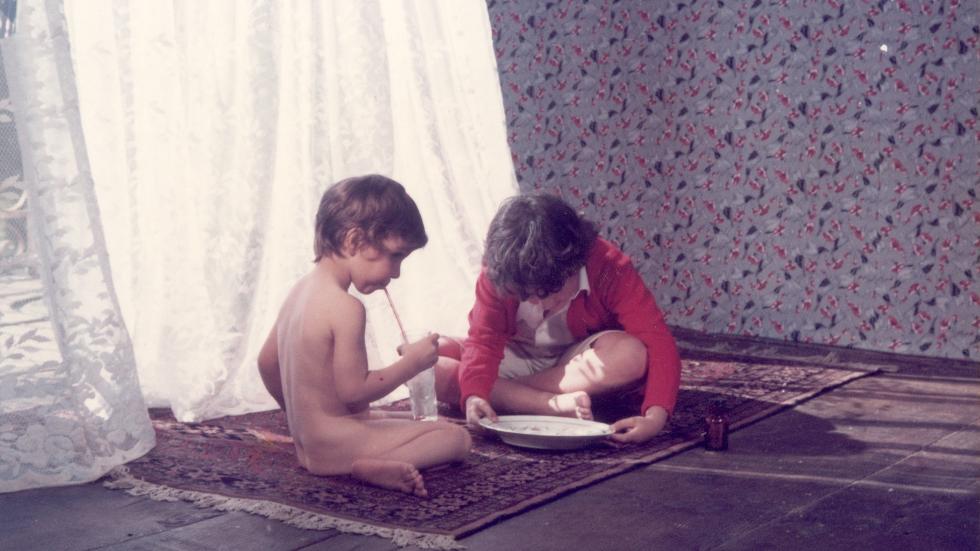

Trás-os-Montes would end up becoming a kind of destiny: Margarida Cordeiro had been born there and it was where they made their first feature length film, to which they gave the same name. Over the centuries the region has arrived at a critical situation both politically and economically, but it remained splendidly inexhaustible in its myths. It had been overexploited and the adults had emigrated, leaving it populated mainly by the elderly and children.

Cordeiro and Reis took on the task of revealing this microcosm in the process of extinction and from then on would never stop working on its material and mythical structure. But that task was also a form of insurrection: “The film isn’t for the city, the film is against the city”, said Reis at the opening of Trás-os-Montes. And also: “The people of Lisbon should remain humble with regard to these people. They shouldn’t limit themselves to eating the bread and drinking the wine from the North East, they should be aware that the region has other riches to offer, more important, more precious.”

The three feature films by Cordeiro and Reis spring from the land of Trás-os-Montes, but the interesting thing is that they leave behind any ethnographic aspiration in order to move provocatively into the terrain of fiction. Because of the boldness of their spatial temporal and narrative inventions, we could talk of anthropology-fiction, trying to create for these films —especially for Trás-os-Montes and Ana (1982), as The Sand Rose (1989) definitely loses its roots, “as if it were the first film to arise from the earth and that speaks about it” (Cordeiro)— a new genre that would do justice to their very complex formal and symbolic structure. Undoubtedly Jean Rouch —one of the great admirers of their work— was referring to this when he pointed out something very evident to any spectator of Cordeiro and Reis’ films, and it is that their labyrinthine surface doesn’t comply with fantasies about reality but rather with the need to reproduce it in a profound, coherent order: “On new roads there appear ghosts of myths that we imagine are essential because we recognize them before we know them.”, said Rouch. Ambiguity that Reis himself had anticipated when Trás-os-Montes was just a project: “No one can know what making a documentary like this would be like. It would involve a hand to hand struggle with ancestral and very modern forms, amidst wolves and Peugeot 504, amidst Neolithic ploughs and gas cylinders”.

Temporal artifices seem natural in Cordeiro and Reis’ films and give the impression of not going against the rules of documentary. “We are a people who live as if time had never existed”, said Manoel de Oliveira about Trás-os-Montes. And indeed from few films like these could you deduce with greater precision this supposed national feature. The overlapping scenes create a kind of stratigraphy, the shots are brief and show the different layers of historic time, which is also everyday time. Reis: “What one learns in these towns is that it is a vice to separate the thousand year old culture, the civilizations that have come after and life today. It is there, in that refusal to separate, where I find a progressive, revolutionary element”.

After the death of António Reis in 1991, Margarida Cordeiro endeavoured to shoot the film they had been preparing for two years, an adaptation of Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo. For the first time, the filmmakers were going to leave Trás-os-Montes in order to shoot in Mexico. Those who know Rulfo’s work —not just the narratives, the photographs too— can grieve, imagining what that novel would have been in their hands. But it was the fate of that last project to remain unfinished, like Que Viva Mexico by Eisenstein. After that, Cordeiro abandoned cinema and went back to Trás-os-Montes, to the house where she’d been born.

Twenty eight years have passed without films by Cordeiro and Reis. Many of those who admired their work —Duras, Daney, Monteiro, Rouch, Ivens, Rivette— are no longer among us to continue inviting us to delve into those works which nourished them so much (Joris Ivens said that, on one occasion when he had to undergo a very serious operation, the last images that came to his mind before falling asleep from the anaesthetic were random shots from Ana, which he had seen some years previously). It is urgent that these films find new admirers. All those which they managed to finish can be seen together in Spain for the first time.