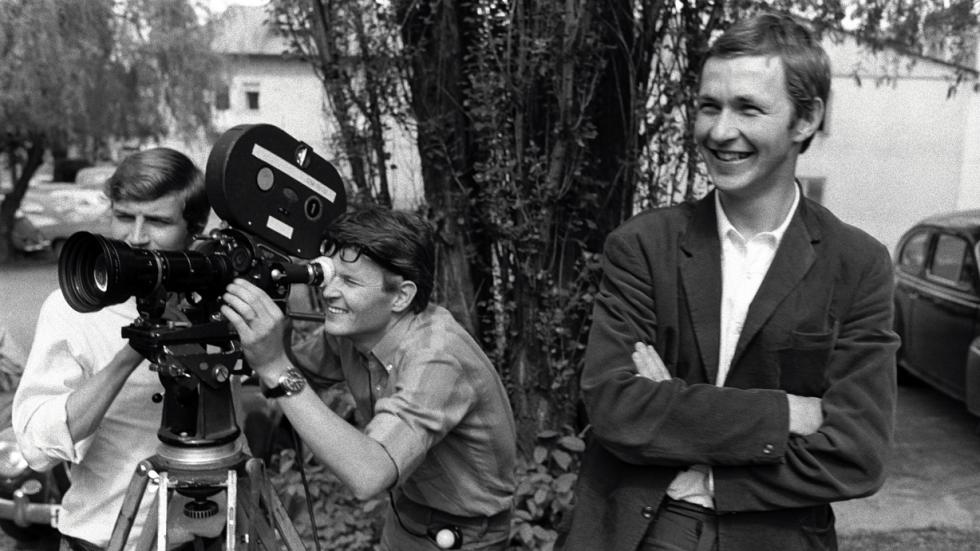

In the 1950s, when film was a mere half century old, the French film journal Cahiers du cinéma convinced the world that film not only had become an art form, but also had its own distinct language—a language of images that transcended national and linguistic boundaries. Over the next few decades, this premise led to the promotion of an elite class of global directors whose mastery of this language—in particular, through cinematic mise-en-scène—qualified them as auteurs. These include Jean Renoir, Luis Buñuel, Frederico Fellini, Andrei Tarkovksy, and Ingmar Bergman, among many others. By the dawn of the twenty-first century, however, technical innovations in filmmaking—in particular, CGI—seemed to have stolen the spotlight from the visionary filmmaker/auteur. It was at this point in cinematic history when Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson (1943- )—who had won global accolades for his debut feature film En Kärlekshistoria in 1970—returned to the big screen with his first feature film in 25 years. Sånger från andra våningen, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2000, won the festival’s Special Jury Prize and near universal acclaim from critics. A powerful new film language was born, and a new stage in the career of one of Sweden’s most remarkable filmmakers had begun.

With Sånger, the first film in a trilogy reflecting on the human condition, Andersson’s vision was to push the boundaries of film language into a new dimension. Fourteen years later, he has concluded this trilogy with En duva satt på en gren och funderade på tillvaron, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival in August. This latest film, the first Andersson has shot with a digital camera, won the Leone d'Oro, the festival’s highest prize and one of the most distinguished prizes in global cinema. (The second film in the trilogy, Du Levande / You the Living, was screened in the Un Certain Régard section of the Cannes Film Festival in 2007.) All three films in the trilogy showcase Andersson’s distinctive film language, one he developed, ironically enough, during his self-imposed break from feature filmmaking from 1985 to 2000.

When Andersson was a young director fresh out of film school, his feature debut, En Kärlekshistoria / A Swedish Love Story won four awards at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1970 and snared Sweden’s top film prize, establishing Andersson as an up-and-coming star and heir apparent to Ingmar Bergman. This first film, a nuanced treatment of young love and the disillusionment of the 1960s generation, quickly secured a permanent place in film history. But Andersson’s next film, Giliap (1985), a dystopic film that captures the grim and purposeless life of a young hotel worker, was rejected by critics and audiences alike, although in recent years, Swedish critics have positively reappraised some of the film’s experimental techniques, such as the fixed camera and the lethargic pace—evidence that Andersson already was experimenting with what would become his own distinctive film language. Giliap bankrupted Andersson, who has subsequently said in interviews that he felt constrained artistically by the production conditions in making Giliap.

Soon, he began accepting offers to make short commercial films for companies ranging from the candy company Fazer, to the insurance company Trygg-Hansa, to the Swedish Social Democratic Party. He became enormously successful, not only in securing wealthy and faithful clients, but also in securing top global prizes for his advertising films, which Bergman himself once deemed the best in the world. With the money he made, Andersson founded his own production studio, Studio 24, in the upscale Stockholm neighborhood of Östermalm in 1980, a move that has granted him creative control over his productions.

His reputation as a filmmaker fully restored, he was approached by Socialstyrelsen, Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare, to make a public service documentary about AIDS. Andersson immersed himself in research about the origin and spread of the disease, and the conclusions he presents in his film Någonting har hänt so rattled the board when they previewed the film that they canceled the commission. Undaunted, Andersson entered the unfinished film in short film festivals, where it captured awards. Soon after, Andersson was invited to participate in 90 minuter 90-tal, or ”90 minutes of the 1990s,” at the Gothenburg Film Festival. The idea was for ten directors to make films that were nine minutes long and commented in some way on the 1990s. Andersson’s contribution, screened at the festival in 1990, was Härlig är jorden / World of Glory, which takes its title from a Lutheran hymn. It won top prizes at seven international film festivals, and in style, themes, and content, it serves as a prelude for his feature films to come.

A SUCCESSION OF BULLETS

While all of his feature films have received funding from government sources and private arts councils, Andersson has also invested a considerable amount of his own money. When trying to secure funding for Sånger från andra våningen, which broke all the rules of conventional filmmaking, Andersson resorted to self-financing a fifteen-minute segment that could be screened for potential backers so that they could apprehend his vision and intent. All three films in his humanist trilogy showcase the distinctive language that Andersson has developed through the years. First, he disposed of a conventional film narrative with a requisite protagonist and antagonist, plot twists, and resolution. Instead, as Andersson described in a project description from the early 1990s in which he sought funding for the film, “we meet an existence that can neither be apprehended nor surveyed, teeming with human destinies, some of which we come to learn a little more about, and they become the film’s main characters. But we will have the experience, not of following these characters, but rather of bumping into them, losing them from sight for a while, then bumping into them again—and again, and again.”

In order to create this experience of “bumping into” characters unexpectedly, Andersson disposes of one of film’s most fundamental techniques: editing together shots and scenes. Instead, he uses a single camera placed at just the right angle and distance from the scene, and has the characters walk in and out of the frame. Andersson’s sets are painstakingly built from scratch, many of them inspired by famous works from art history or by iconic photographs, and Andersson uses a technique from cinema’s earliest days—the trompe de l’oeil—to create the illusion of a far greater depth of field than what actually exists. Each set and scene serves as a self-contained vignette that is woven together with other vignettes, which means that the viewer never knows exactly where s/he will be taken next, or who will be there. In the spirit of the auteur, Andersson writes all of his scripts himself, and the dialogue fuses the nonsensical trivialities of everyday life with stark, philosophical statements, rendering “natural” speech unnatural.

The final element of Andersson’s distinct style is his casting of amateur actors almost exclusively, as he believes that professional actors are too polished and self-aware in their gestures and the delivery of their lines. To lessen distinctions between characters, indicating that they collectively are bound together as humanity in the mass, the actors wear similar clothing colors and have white makeup smeared on their faces. The resulting mix of meticulous mise-en-scène, lumbering dialogue, and almost naïve acting results in an on-screen effect of spontaneity, playfulness, and unforgettable moments of dramatic irony.

tribute to CERVANTES

Philosophically speaking, there is a common thread that runs through all of Andersson’s films. Andersson is worried about the state of humanity, about humans’ capacity for war and genocide, human greed and indifference, and human fraility. As his films show, even those who try to do the right thing find themselves overwhelmed by the senseless cruelty and stupidity of the world around them. Buñuel’s film Viridiana (1961) contains such a seminal scene for Andersson, when a man buys a dog to save it from having to run underneath its former owner’s horse carriage, only to be met with countless other carriages with similarly suffering dogs. The films in his humanist trilogy draw visual inspiration from the world’s great artists, among them Francisco José de Goya, Honoré Daumier, and Otto Dix, and the bookcases in Andersson’s studio are filled with art books. But Andersson turns to great literature for the films’ humanist ethos. Sånger was inspired by César Vallejo’s poem “Traspié entre dos estrellas”; in fact, according to his own filmography, Andersson began a film in 1978 that he tentatively titled Älskade vare de som sätter sig (the Swedish translation of “amandas las personas que se sientan,” a refrain from Vallejo’s poem), but set it aside, only to have it evolve into Sånger two decades later. Du Levande was inspired by Goethe’s 1790 Roman Elegies. And En duva is an homage of sorts to the great novelist Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra; the film takes us on a journey of trivial moments with two hapless characters whom Andersson describes as “modern times’ Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.” The director describes it as a film that “shows us the beauty of single moments, the pettiness of others, the humor and tragedy that are in us, life’s grandeur, and the fraility of humanity.” It is precisely such tragi-comedy for which Roy Andersson has become known. While Charlie Chaplin was arguably the most skilled practioner of this art in the early twentieth century, Roy Andersson has breathed new life into it for the twenty-first.