Events, life, and things pass over us like a confused mass, we do not live according to an orderly narrative, and it is only possible to blindly react to what happens day after day without knowing where it will lead. Films are not like that, there is planning in them, an issue with an outcome - everything happens for a reason. Images in movement have the ability to elaborate a coherent narrative originating from that confusing material that reality is, and because of that same reason, they also have the power to show themselves as irrefutable proofs, raising themselves as unquestionable truths. The visual artist Lene Berg (Oslo, 1965) has been examining the two sides of this coin since the early nineties, with films of an unusual conceptual and formal knowledge. The construction of a story (depending on the case, may be dissident, ironic or uncomfortable) through the embroiled elements provided by experience, history and knowledge seems to be her specialty. Like the one who builds the plea of a trial, Berg unfolds before us clues, proof, and evidence. Elements that, connected by her thought, her visual imagination and her sense of montage, articulate a tale of the real inquisitor and thinker (often dismantling established and never questioned discourses) at the same time as they delve the unquestionable suggestive power of cinema.

These "allegations" by Berg are not neutral choosing their themes and subjects. If we take a look at many of the pieces in the spotlight, they all share an eagerness to test the limits of ethics, and many of them also show a willingness to bring voices to the front that have not yet been taken into account - forgotten stories that, consequently, remain invisible and it implies. To displace the speech of the dominant power by those dominated by it. It is in this way that her cinema breaks down three barriers: the one we pointed out before, the implicit plausibility we give to audiovisual narratives, the validity of shared ethical precepts (without being deceived by flat notions of political correctness), and the beliefs that there is one and only truth (the one narrated and spread by the current power).

Berg's formal strategies to achieve these goals move smoothly between the real and the fictional, with a strong tendency towards staging in its most diverse variations. A staging that in some cases can be developed through editing and voice-over, as it is done in THE WEIMAR CONSPIRACY (2007). In this amusing and inquisitive piece, Berg takes what could be the record of any tourist of a string of visits to the houses of illustrious men and monuments of Weimar, providingit with a structure and adding a spoken narration. Weimar, let's not forget, is a fundamental spot in German history. It was home to writers such as Goethe and Schiller, philosophers such as Nietzsche, and a hot spot during the Nazi years. The voice-over shows us a visitor who ignores all that past while roaming through a theatrical place emptied of content to serve tourism. The result is two-faced analysis: on one hand, the validity of the legacy of this historical and cultural heritage, and on the other, the banality in this way of preserving and spreading it.

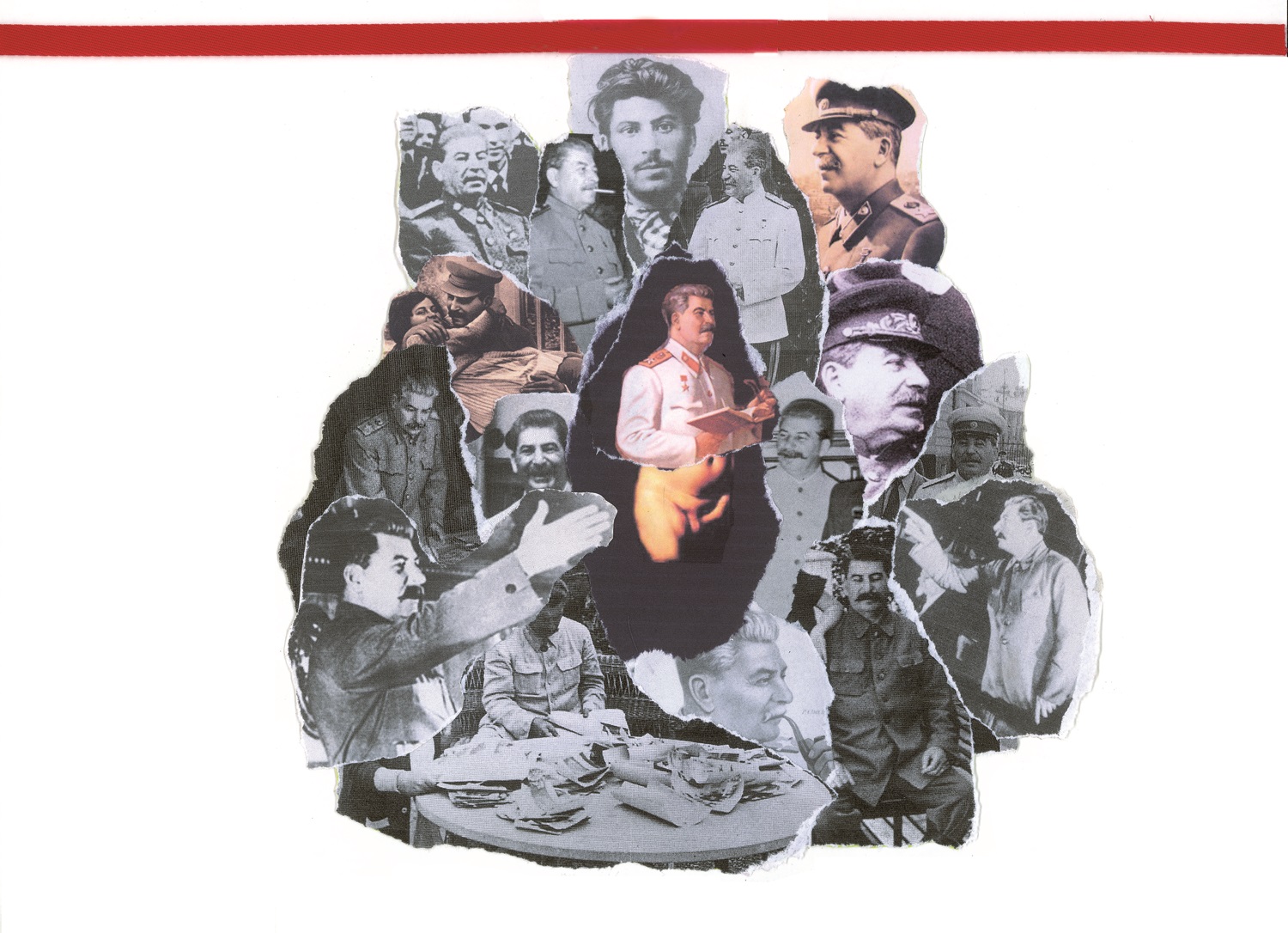

One of the most fascinating versions of staging in her cinema is a very particular collage work that operates on the margins of animation without exercising it. Berg works with photographs, cuttings, and drawings in interaction with her voice-over, in a sort of " facts reconstruction" (following the criminalistic simile); events that could not be filmed, overcoming the obstacle of the impossibility of narrating them through the cinema. Collages that are not a simple complement but produce new meanings and open new dimensions of narration (retaking on a traditional collage strategy: unusual collision of images to produce new meanings).

Take, for instance, STALIN BY PICASSO OR PORTRAIT OF WOMAN WITH MOUSTACHE (2008). A piece on the controversial portrait of Stalin painted by Picasso structured in acts, where each one is headed by a different version of "The International" (which ends up generating a humorous effect). The whole piece is composed of static material: clippings and figures made by Berg, printed texts, photographs, newspaper reproductions, different textures and colour papers that appear before the camera, sometimes with Berg's hands manipulating them. The comic vibes of some sections and the collage give an ironic touch to a story that is no less ironic and contradictory. Picasso, a well-known communist, draws Stalin at the request of Louis Aragon to illustrate the cover of a famous party newspaper. But, things in life, communism in Stalin's time rejected the art of many of the artists who supported the cause, the members of the European avant-garde, as it considered only socialist realism valid. There is thus the paradox that a drawing that was intended to be a tribute is branded as a caricature, and it is precisely this conflict that turns the image into myth. Berg reconstructs the facts, the before, the during and the after of the story, staging before our eyes an analysis around the relativity of aesthetic ideas, the conflictive relationship of art, power and propaganda, and the influence of an image that - as he narrates us - was even able to send a common man to a forced labour camp just for having it hung in his kitchen.

Berg's latest work, FALSE BELIEF (2019), recovers this formal strategy to deal with a contemporary issue directly related to her personal life. On this occasion, it speaks not only of the power of images but also of the long tentacles of economic interests, the constant surveillance in which we live immersed, and the use of political correctness.

The film consists of a series of on-camera testimonies by D. (Berg's African-American editor partner) and several collages through which Berg narrates, in a voice-over, the twisted Kafkaesque events that end up taking D. to prison without having committed any crime other than walking through his neighbourhood park. The photographs of the Harlem part of New York, where the events take place, function as deception of the real, an illusion that is broken when Berg places other photographs on "the scene of the events," clippings representing those involved, as well as documents and evidence of different kinds. An (anti)police statement that takes note of the tremendous injustice that put in check the life of a man on account of the shameless economic interests of upscaling. The accusers are a homosexual couple who make a series of false accusations against D. Accusations based on evidence such as the dubious testimony of the accusers themselves and visual evidence such as a copy of a photograph whose composition and content pose more ambiguities than certainties, and which are open to thousands of possible interpretations. Berg thus orders the chaotic nightmare of which D. is a victim in a plea with evidence as valid as that of the accusation while denouncing a corrupt system that uses members of historically discriminated social groups (such as homosexuals) as the frontmen of an enormous economic network. A difficult to solve ethical and moral trap.

False Belief has two themes that are addressed by one of Berg's most famous works at the Venice Biennale, DIRTY YOUNG LOOSE (2013). These themes are the society of surveillance and prejudices grounded in the collective subconscious. In this case, Berg proposes her reconstruction of the facts as a fiction that recreates the supposed images taken by the security camera of a hotel room. In this room, a young man and woman interact with a mature man. The action is repeated three times, once for each of the interrogations of each of the characters, stopping or accelerating different parts. The interrogators set in motion the whole battery of clichés available for each one of the characters, the mature man on a business trip, the woman in her thirties and

the young man astray. The images can thus be successively the irrefutable proof of each one of these truths, that of the interrogators, and that of every one of the interrogated.

The subject of monitoring is central to GOMP: TALES OF SURVEILLANCE IN NORWAY 1948-1989 (2014), a kind of television audience in which we hear the testimonies of a group of citizens who were under surveillance or vigilantes themselves during the Cold War years. Berg allows himself a humorous beginning as a tribute to the spy films of the sixties before moving on to the courtroom. Statements are either accounts told directly by their protagonists or the narrative interpreted by actors of the experiences of those who didn't want or couldn't go to the shoot. Throughout the testimonies and thanks to Berg's montage, an analysis is being drawn of the consequences of this surveillance among civilians that can only lead to Foucault's panoptic, while simultaneously revising the history of Norway after World War II. Lighting an elegant visual approach that completes this sober and forceful painting.

Following this line of quasi-theatrical staging as a context for real testimonies, KOPFKINO (2012) proposes a sumptuous table whose food looks like carefully composed stilllife paintings in an empty theatre. The long table - reminiscent of the Last Supper and The Exterminating Angel - is the place-non-place where eight women who engaged in sadomasochism share all sort of experiences they had with their clients. A slow lateral traveling goes from one side of the table to the other throughout the film during the conversations; a servant with his ass showing serves them, while two dogs prowl around. Besides being a fascinating evening with access to unusual information, it is interesting to see through each anecdote a sort of sexual theatricality about human power relations. Three submissive and five dominatrices tell stories between bewilderment and humour, in which we rock through the sumptuous and velvety forms of the film. "Kopfkino" is a German expression meaning "mental cinema", that is, the mental staging of our deepest desires and fears. Berg seems to play with this expression: on the one hand, let us imagine what we hear at our leisure, and listening to the testimony of those who bring to reality the bizarre fantasies of their clients.

Through this tour, it is easy to see that Lene Berg never stops asking questions. Uncomfortable and difficult queries that often pose the ambivalence of our most deeply held beliefs. All of this is interwoven with the dilemmas of her artistic practice, that does not hesitate to question itself or to expose its mechanisms to wake us from our credulity. In this reconstruction of the most varied facts that is her cinema, stories constructed through clues, proofs, pieces of evidence and testimonies, there is space to put in question the images exploiting all their power. Also to unleash the power revealing its darkest and most bizarre ways of proceeding.