The New Waves is undoubtedly one of the liveliest sections in the festival. The lightness of the titles chosen, which rather than stating categorically, question, dance and slip inquisitively along little-travelled paths, shows the adaptable, daring, constantly mutating panorama of European cinema. It is the propitious space for detecting signals, discovering talents and following the steps of unclassifiable veterans. It is a real playground, in which to venture in search of surprises.

QUESTION OF HUMOUR

It seems that European comedy tends to look at itself and be self-reflexive in its forms. For example, in the two films that open this section, two film directors fail in their attempts to make a film. Filmmakers played, in addition, by the respective directors of the “real” films: Carlo Padial in ALGO MUY GORDO and Julian Radlemaier in SELF-CRITICISM OF A BOURGEOIS DOG. Padial’s case is framed in something that has given rise to a lot of talk, posthumour, in which priority is given to a perplexed, eccentric comic style that also tends to reveal the act of creation in its different manifestations. Announcing with a great fanfare a film that will be “something very big”, “revolutionary” and with lots of “CGI”, starring a successful television figure (but open to risks) like Berto Romero, Something Very Big talks in making of style of the failure of this undertaking, resorting to the personal quarrels, jealousies and egos of those involved in the film. It is also an ironic commentary on the false idea of progress, which thinks that the renewal of forms goes hand in hand with technology.

Radlemaier’s film, on the other hand, never even gets started. The Julian in the fiction doesn’t manage to get the money to finance his film. Although he wants to hide behind the figure of a committed, Marxist filmmaker, he always acts for much more mundane motives. It is nothing other than a satire of a world of art that is always politicized and committed to reality, but from the vantage point of a bourgeoisie that refuses to contemplate its navel. Going along the paths of the absurd, the magical and the laconic, the final destination of the antihero of this film turns him into the “bourgeois dog” that he is, literally.

REQUIEM FOR MRS. J., by Bojan Vuletić, is a caustic view that takes very dark events as the reason for its comicalness. A woman depressed a year after her husband’s death who plans to commit suicide on the anniversary of his demise. Vuletić seems to tell us that in a grey, godforsaken Bulgaria, it isn’t possible even to kill yourself in peace. The Mrs. J of the title has to deal with a string of bureaucratic formalities, waiting rooms, lazy government officials and run down institutions in order to leave her affairs in order. So much so that, paradoxically, perhaps that same disastrous ineffectiveness may be capable of restoring her will to live.

In the case of BEFORE SUMMER ENDS, by Maryam Goormaghtigh, the disenchantment comes through an immigration seen from a rather unusual perspective: three young Iranians who travel through the south of France to say goodbye to one of them who is going back to his country after studying in Paris. On the summer nights, and on the car journeys, we get to know the contrasting feelings of the young men: homesickness, combined with the possibility of being themselves that is offered by the new country. The comparison with Stranger Than Paradise which Jordan Mintzer sets out in Hollywood Reporter is more than precise: the film deals with a group of social misfits full of private codes to which Goormaghtigh’s distinctive view gives an aura similar to Jarmusch’s characters.

Also sensitive to humour, but coming from a different tradition, are the films by Serge Bozon and Jean-Charles Fitoussi. Members of a select club of contemporary filmmakers, heirs of filmmakers like Vecchiali, Guiget, Rivette, Rozier and Arrietta, among others, whose time in various New York institutions in 2011 led to them being called “free radicals”. Both also share, in this case, their roots in fantastic literature.

Bozon is one of the most active, omnipresent figures in the group, not only as a director but as a critic, screenwriter and actor. MRS. HYDE is his particular version of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Robert Louis Stevenson, in which the protagonist here is a timid teacher in a technical high school played by Isabelle Huppert, Madame Géquil. The social satire of contemporary France (with a touch of sarcasm towards the self-righteous mentality, especially in the fearful transformation into Madame Hyde) is present through some characters with a subtle caricature-like touch. The aesthetic game and the absurd (a very lucid absurdity) round off this new work by Bozon.

In the case of Fitoussi, we escape to a microworld, a castle, with a cast of characters almost from Cluedo. VITALIUM, VALENTINE!, the latest instalment of his particular filmic serial, his series of films Le Château de Hasard, springs from the figure of Frankenstein. The macabre mingles with the burlesque. Terror with romantic mix-ups. The owner of the castle decides to kill his whole family, in order to sell the castle with the dead bodies included, to one William Stein (grandson of Frankenstein), who experiments implanting the DNA from his family ancestors (in the catacombs) into the “freshly dead”. A DNA that comes laden with memory and romantic quarrels. Fitoussi sets his fantasy in motion with the game of representation and a perplexing mise-en-scène.

WITH YOUR FEET ON THE GROUND

Another aspect which is starting to be a tradition is hybrids between fiction and non-fiction. In general, they are films in which the social reality from which they begin is indissoluble from the story, in which showing ways of life is an essential part of what is expressed, and humanism is situated in the foreground.

That is the case of the background work carried out by Adrian Orr with NIÑATO. A film that is both a sequel to and an extension of his 2013 short film, Good Morning, Resistance, in which he already showed the particular family of David Ransanz, the “niñato” of the title, a young rapper from the outskirts of Madrid who is rearing his three children without a job and living with his mother. Through day to day life and close coexistence between the filmmaker and his subject, Orr draws a portrait of a figure who is trying to hold out in a grey, discouraging panorama, of the way in which he’s rearing his children, and of how he persists with his musical dreams. Fleeing from gruesomeness, pathos or emotional traps, he manages to move the viewer and transmit closeness to his subject, observed at the same level.

In UNDERGROWTH, by David Gutiérrez Camps, the daily life shown is that of Musa, an African immigrant, and his strategies for surviving in a town in Gerona. Much more introspective and silent, Undergrowth pays close attention to the work of clearing weeds, gathering firewood and pine cones in the solitude of the forest. His contact with the neighbours is always shown with a certain distance, revealing the alienation of someone to whom no door is ever really opened, even if he isn’t faced with full-on hostility. At one point, Musa, with an African friend, sees an ethnographic documentary on his country. Something that seems to be a nod to the distant, outsider way in which he looks at his surroundings, especially obvious when he observes the dances and rite of the festivities in the town where he lives.

In THE INTRUDER, Leonardo di Costanzo stays in his Naples, working with the inhabitants of the outskirts, and that starting point anchored in reality is dramatised through the figure of Giovanna, who runs an occupational social centre for children, a particular Antigone in this story. The dilemma that occurs is used to comment on a current social problem: the collateral damage left by the mafia, always offscreen. Giovanna unwittingly takes in the wife of a mafia gangster and her children, and when the husband is taken prisoner, the woman decides to stay and distance herself from her in-laws. Giovanna defends “the intruder”, but the rejection by the community shows the difficulty of reinsertion and the limits of tolerance, in a world in which stigmas, resentment and fear prevail.

In MILLA, Valérie Massadian takes us to territories that are more intimate but also on the margins of society. With a strategy similar to that of Nana, she manages to submerge us in the introspective sphere of her character. The story begins with a pair of runaway adolescents, living from day to day in places where they manage to squat. After the tragedy that shatters their love, we stay with Milla. A character with whom we face a tremendous setback, mourning, endurance and personal reaffirmation, the passage to adulthood and the independence of a single mother. Through the observation of daily life, letting the light and situations rest, Massadian takes us through the story without wild gesticulations, and even allows herself to break the realism on a couple of occasions.

A REALITY THAT FRACTURES

It is precisely in unexpected ruptures and changes of direction that the films in this section move. Films that talk about pressing matters, but choose less travelled paths to do so.

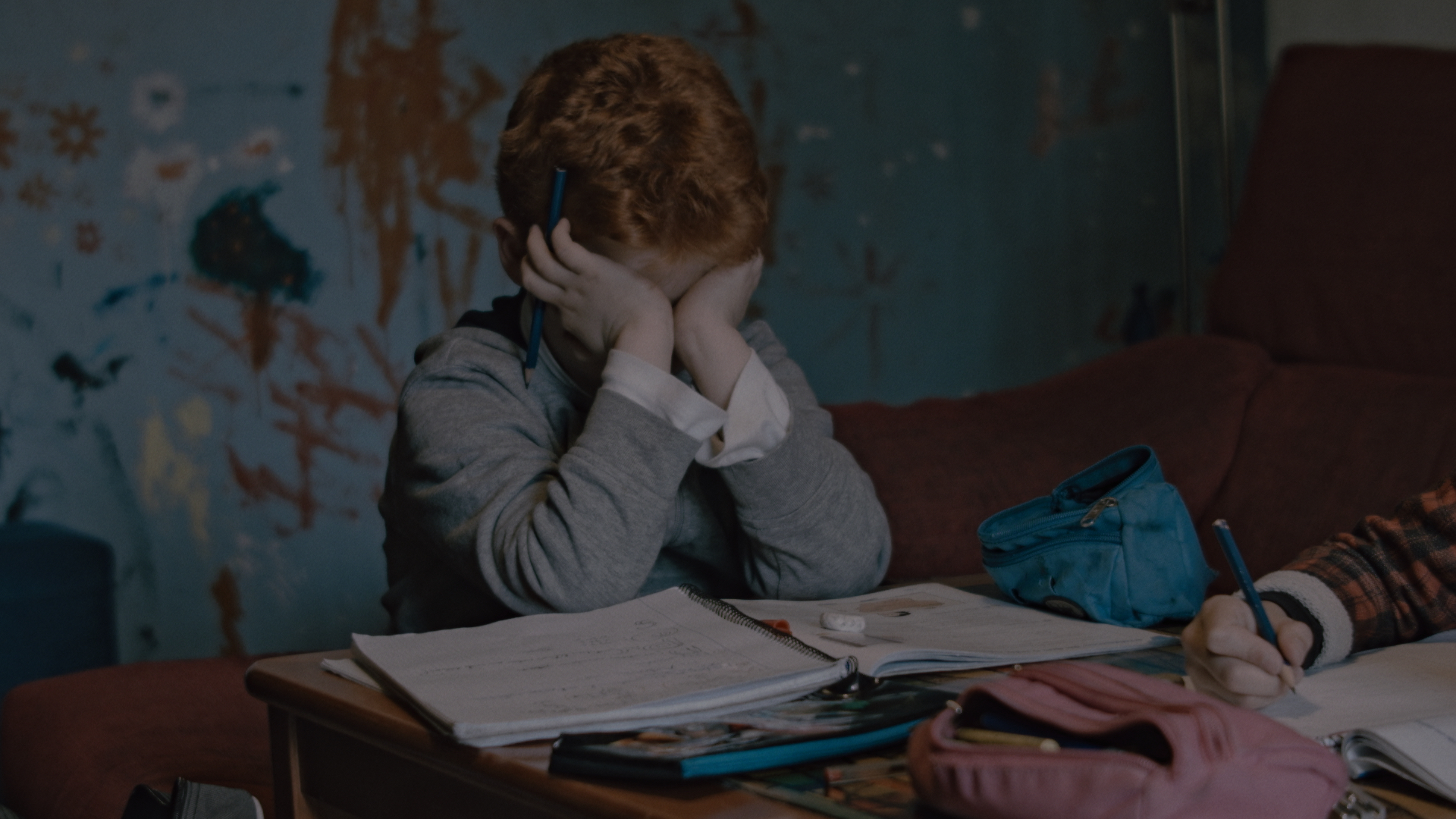

COLO, the eagerly awaited film from Teresa Villaverde, deals with well-known factors from the Portuguese financial crisis: a family of three, the father unemployed, the mother working double shifts and the daughter rebelling at the lack of perspectives. Villaverde, however, chooses to leave financial hardship as an underground current in order to focus on the break-up of a family that faces the circumstance by retreating into their own individual worlds. We are presented with two particular withdrawals, that of the daughter and that of the father, who break their routine to end up wandering through nature, in another reality far removed from theirs. A lot of questions arise about relationships between the traditional family, capitalism and consumption, and about the direction personal matters have to adopt in the world we are facing.

THE GULF, by Emre Yeksan, takes us to Turkey, specifically to Izmir (Smyrna). There, another result of the times we live in: a thirty year old who, after failing at work and in his relationship, goes back to his parents’ home. The film goes from talking about things generational to dealing with things political via things supernatural, when a terrible smell spreads through the city and forces the inhabitants to flee: a metaphor for the suffocating atmosphere in contemporary Turkey. Our antihero stays, after his family has fled and his house is taken over by the family of their maid, in an atmosphere of emergency and peaceful revolution.

SICILIAN GHOST STORY, by the Italians Fabio Grassadonia and Antonio Piazza, gives a supernatural twist to a violent story of the Sicilian mafia: the kidnapping of 13 year old Giuseppe Di Matteo, who was held for 779 days and then murdered in 1993. The reason, his father was informing on his criminal companions. Grassadonia and Piazza (who in Salvo already brought an unusual viewpoint to this subject) build a kind of fairy tale, full of spirits who manifest themselves by means of framing and camera movements, and with an exceptional use of sound, that is also a love story. A twist far from frivolity that manages to move the spectator and offer a heart-felt tribute to the victim.

HERSTORIES

There is another current which, to judge from a handful of recent films, is starting to become more visible and relevant within the panorama of European cinema: the contribution of a new generation of directors to what has been called “coming of age tales”. Adolescence, and sexual awakenings, told on multiple occasions from a male point of view, have in the last few years been finding their counterpoint. Three first films show this, the adolescent as a subject instead of an object.

On the one hand, AVA, by Léa Mysius, starts from a devastating piece of news. Ava, aged 13, and on holiday with her single mother and her little sister, will go blind in a short while. Her way of dealing with this is through recklessness, in a headlong rush towards wildness. In a film where the body and the senses are important, adolescent sexuality is revealed naturally and without reservations. Ava seems to be seeking the knowledge of the body and a visual repertoire to store in her memory, while learning to embrace darkness (an idea that has its echoes in elements of the film, like the black dog, the cave where the boy, the object of her desire, lives, or her mother’s lover).

The sexual awakening in PIN CUSHION, by the British director Deborah Haywood, is more perverse and is much more measured. Haywood takes a series of classic elements from films about adolescents (as they’ve been conceived since the ‘80s): roles in high school, popularity (and its price), embarrassing moments, competitiveness, teen perfidy, the importance of clothes and make-up and a certain pop aesthetic. A now classic story that here leans towards its dark side (without abandoning the colour pink and cheesy aesthetic), where each step in the discovery of sexuality and access to maturity is marked by a merciless (and caricatured) social plan. The extravagant tone and a jumbled aesthetic complete the construction of the suffocating (and magnetic) world of the film.

SARAH PLAYS A WEREWOLF, by Katharina Wyss, isn’t exactly a film of passage to maturity but rather its antithesis. With a frugal, precise tone (whose Bressonian roots are revealed especially in the final sequence), it is a film that suggests instead of showing, and prefers to amplify the terrible magnitude of the underlying theme and let the spectator work. An adolescent from a cultured, well-off family starts behaving in an excessively exalted way as a result of drama classes. The classes make it possible for her to release what is inside her without “being her”, but her manifestations are too dark and violent for her surroundings. A sorrow (and a secret) that she can’t articulate, and to which the cinema manages to give ineffable body.

ANOTHER TURN OF THE SCREW

This final section contains unclassifiable proposals, fruit of distinctive worlds that bring genres and various film references to their own ground.

In 9 FINGERS, F.J. Ossang goes back to the aesthetic of classic cine noir and gives it punk, industrial and retro futuristic airs. Echoes of Melville, Lang, Tourneur or Reed, recognisable codes that bathe what is apparently a detective story, full of comic strip characters, that becomes more and more cryptic and elliptical, and seems to be the expression of a mental state, turning increasingly in on itself. 9 Fingers seems like a bad dream full of magnificent images, which also follows the mysterious logical dictates of that expression of the subconscious.

Also with a bizarre story, a journey by boat and a large part of the film in black and white, THE WILD BOYS, by Bertrand Mandico, is presented as an adventure film, a kind of disconcerting sexualised The Lord of the Flies. The group of boys who feature in it, and who are punished by being sent on a trip with a Dutch captain, are played by women. With an aesthetic that brings together Guy Maddin, Derek Jarman and the Fassbinder of Querelle, the adventure ends up taking them to an island with transformative powers. Artificial genitals, plants that screw, trunks that ejaculate, hairy fruits, in a representation of the fluidity between surreal sexes, imaginative, explosive and brilliant.

In HELPING THE HUMAN EYE César Velasco-Broca and the Canódromo Abandonado collective (Julián Génisson, Lorena Iglesias and Aaron Rux) come together in the creation of a modular film, in permanent process, with pieces that keep changing and revolve around the character of Father Julián played by Génisson. A manual of esotericism and exoterism of unclassifiable aesthetic and humour (that ranges from a short film in black and white on 16mm to another flooded with chroma keys and internet aesthetic), which on this occasion is made up of 4 parts: a British ‘70s TV movie about the prevalence of evil (Nuevo altar/New Altar),a segment about an Olympus of gods of the Spanish autonomous communities (Dioses autonómicos/Autonomous Gods ), the story of a nurse who attacks men who then suffer a terrible humiliation (La enfermera atracadora/The Attacking Nurse), and finally Nuestra amiga la luna/Our Friend the Moon, the short film we already saw last year at this festival, a free interpretation of the gnostic text of the III century, The Hymn of the Pearl.

By Elena Duque