There is a mystery in La Point Courte that I haven’t clarified yet: What made me consider making a film? I didn’t know what cinema was, first of all because I didn’t go to the cinema. In fact, I believe I approached La Pointe Courte as if I were writing my first novel, without worrying about if it would be published or not. I used to read a lot at the time, and a kind of literary filiation can be clearly seen: the film was directly inspired in Las palmeras salvajes. Not much with regard of the anecdotes, but in construction terms: the shifts from the couple’s story to the Mississippi rises. That was not allegoric neither symbolic, but there’s a sense emanating, discernible from the mixed reading of those two stories. I really liked that suspense impression, quite irritating when reading and then extraordinary. Thus, it’s the reader who should have the capacity to reorganise the feelings.

La Pointe Courte is a rehearsal of a film to be shot. It is made from the mix of two chronicles –one is the story of a couple after four years of marriage, the other is about a fishermen village–. Both stories never intermingled, but audience could contrast them or even superimpose them. This was a time in France when people started talking about “the distancing effect”, about Brecht, etc. I hadn’t read those theories yet, but the possibility of playing with the audience’s not-identification with a film character fascinated me.

One day, Anna Sarraute introduced me to a nice young couple, who worked in film and had shot a short film: Carlos Vilardebo and his wife, Jane. I told them about my idea of filming, I explained my ideas. I had never seen a camera. Carlos told me: “You will need someone’s support, someone a bit known, that can take care of material issues”. He kindly proposed himself for the job with his wife as script. He immediately put together a team, and a small cooperative was constituted, where each one had its part. Resnais, the film editor, was also part of the cooperative. He told me by then: “We have to show the film to a couple of persons in Paris that ‘feel’ the cinema better than anyone: André Bazin and Pierre Braunberger”. We arranged a screening for them. Braunberger found it interesting, because his nose is ready to smell anything new: he was happy. But it was Bazin the one who managed recognition for La Pointe Courte. He told me we had to show the film at Cannes and I followed his advice. I went to Cannes, left the reels in the station’s left-luggage office, met Bazin at the Palais and he proposed me a list of guests. And then came the day, and there were so many people. I got very good reviews, especially the ones by Bazin and Doniol; they were saying really interesting things and even mentioned the rise of a new cinema.

I remember that Resnais, during the editing, used to say: “Look at that, it reminds me of La terra trema”, or, “There’s a shot that resembles Cronaca di un amore”. Eventually, I thought that I had to go and see the things he often mentioned, and so I started to go to the movies, to the Cinémathèque, to attend film premieres, to buy magazines. I really discovered the cinema when I was 26 years old… editing my own film. Then I realised I wanted to be a filmmaker.

Braunberger called me to a meeting and said: “—I’m going to do everything I can so you can make films. —Excellent. —I have an assignment from the Tourism Department, about the châteaux of the Loire”. I thought I was going to hit him. I told to myself: “He must despise me, after the La Pointe Courte the châteaux of the Loire…” Finally, I went to visit those famous castles with my heart full of sorrow. But I found there a sublime end of autumn; everything was golden, blurred by the sun… I was drawn by the sweetness along the Loire river.

They were completely satisfied and asked for “more”. “The Côte d'Azur, if you please”. I told to myself that it couldn’t be possible, that very soon would be the Limousin, the Périgaud, etc. But I’ve gone ahead a little bit. After the O saisons, ô chateaux, I filmed L’Opéra Mouffe. I was so upset for having shot a film on demand that I took comfort in filming with a 16 mm. Paillard. Filming something more personal came to me in a time I begun to observe a casual change in my look or sensitivity. As I was pregnant by then, the film came to answer the question: What can be the viewpoint of a pregnant woman in the Mouffe neighbourhood? It’s the contradiction between the feeling that the Universe should be a universe of hope, and the true desperation.

I went everyday to the market at the Mouffetard street, carrying an iron folding chair, to stand on it and look. I used to place the chair in the middle of the street which, as you know, is an uphill street: my tripod and my camera were slightly above me while I filmed. Nobody noticed me, as I was there the whole time; after two days, just the same as a lemon or bread vendor, I was part of the set. I filmed everything I wanted for a month. I worked according to a series of chapter titles: the pregnancy, the willingness, the alcoholism, etc. As for what I was filming, I knew to which category it would belong and fit. It was like the great melodic lines. Some mornings I felt inspired by drunkenness; some others, by tenderness. I just had to choose the right thing depending on the mood I was experimenting. Obviously, this method involves a large selection process.

I liked to deal the confusion, right in the middle of the Mouffetard market, between having a baby inside my belly and have it full with food. And then, contradictions. A pregnant woman looking at the people as they flock to an uphill street, especially elderly people, and thinks: all of them, old people, one-eyed persons, tramps, all of them had been babies once, often beloved new new-borns, who had had their bellies kissed, their bottoms dusted… It’s the kind of thought that pushes the look to the limits of cruelty and tenderness. Out of all the films I’ve made, L’Opéra Mouffe is the one I prefer, the freest one. It’s placed in that limit I take so much interest in between shyness and shamelessness. It’s the first film I felt I was working for this great job of filming.

I wanted to make an essay on tourism for my second order, Du côté de la côte. Why do people go to the Côte d’Azur instead of going anywhere else? It’s Anatole Dauman, the Argonaut, who receives from the tourism department the order to shoot a documentary about the Riviera. He summoned me, and there I go, looking for locations, this time in Nice, Cannes and Menton, Blue Guide in my hands and a Rolleiflex hanging around my neck. I chose exoticism: the Russian church in Nice, the mosque of Fréjus, the exotic gardens and the private villas, with private sculptures in private gardens facing the sea. The small village of popular tourists has been deprived of it all, except from the sea. I was trying to understand what made tourists -including campers- run to this imitation-jewellery Eden.

I like to laugh (at first, I wanted to title the film Eden-toc [Eden of imitation jewellery]), but the irony implies that we make fun of others. Once an order has been accepted, it is better not to get bored. The real target is to obtain a second degree, not so much of irony. When watching Du côté de la côte, people enjoy it, but in fact is not so fun. The film is related to a kind of observation principle, of explanation by means of indulgence, which is well indicated in the commentary. The idea was that people seeks a kind of Eden, to which they have the right for, since they are tired. And it’s not their fault if the proposed Eden in the coast is made from imitation jewellery. But whatever the case, that Eden of imitation jewellery contains the idea of rest, which is beautiful, a basic idea. One must be indulgent and look at people like it’s seen in the film. At the beginning we laugh; then we understand.

With Du côté de la côte I found my taste for commissioned films. The limits of a given subject, the motivations of limited partners and the ambition of producers excited my desire to honour the order, repairing it a bit, introducing personal subjects and making people laugh and smile as much as possible. It helped me become aware of my attraction for playing with images, for words and acrobatic comments, thus making the editing easier. I had also experimented with movements and rhythms.

When Godard finished A bout de souffle, Beauregard told him: “Do you happen to have any colleagues with the same style?”, and Jean-Luc sent Jacques [Demy] to him; when Jacques finished Lola, Beauregard asked him: “Do you have any colleagues with the same style?”, and Jacques sent a little partner to him, and so I showed La Mélangite to Beauregard. “We can’t film that”, he answered, “but your friends tell me you are good at this, so if you think you are able to make a film with less than fifty million francs, then you have carte blanche”. This budget obliged me to shoot in Paris, with just a few characters.

Cléo de 5 à 7 is a film shot while waiting to make another film… I have the feeling I’ll make a career waiting for Godot. I used to go to Parc Montsouris at ten in the morning, at eight in the morning, at five in the morning… until the light on the grass created a kind of deliquescent whiteness which really interested me. White is a fascinating colour in which my own vocabulary persists. The same way writers have their privileged words, I have my word-images, they appear in all my films. Hence, everything related to love find their expression in whiteness: white sand, white sheets, white walls or white paper. Such things, like the relationship between a feeling and a place, are the ones I especially work on. There’s a solution in whiteness that, for me, is Love and is Death. It is neither symbolic nor systematic. It’s just images that arise for themselves, they come to me. In Cléo, the whiteness is tragic: it is not the obscurity absorbing the life, but the brightness dissolving the existence.

The camera does not abandon Cléo from five to half past six in the afternoon. If time and running time are true, so are the journeys and distances. Inside this mechanical time, Cléo experiments a subjective duration: “time lasts on her” or “time stands still”. As she herself says: “We have very little time left” and, the next minute: “We have all the time we want”. I found it interesting to make this movements be felt as alive, ingenuous, like altered breathing, inside a real time which seconds are measured without fantasy.

Salut les Cubains constitutes a tribute to Cuba. I was invited to go by the ICAIC. I took with me a Leica, some film and a tripod, because I already had this project in mind. I wanted to show, among other, the origins of the Cuban music: African, Haitian, French, and Catholic. I asked Sarita (Gómez) and some other young authors, technicians and operators of the ICAIC to come dance a cha-cha-cha on the streets of a very popular neighbourhood. A small, wobbly tripod was my only support and the Leica forced me to rearm twice, in other words: a few seconds passed between shot and shot. Instead of reconstructing a continuous movement by filming images close to each other in time, we were only able to reconstitute a continuity full of potholes, which gives the film a rhythm of cha-cha-cha, bolero, danson and guaganco. I took 4,000 pics, of which I mounted 1,500 during six months, but I obtained a reward: in Cuba, they said it was a Cuban film; it had the “flavour”. And for them, when you can find the “flavour”, then you are a Cuban. They make programs with my films; they call them “Salut Agnès”…

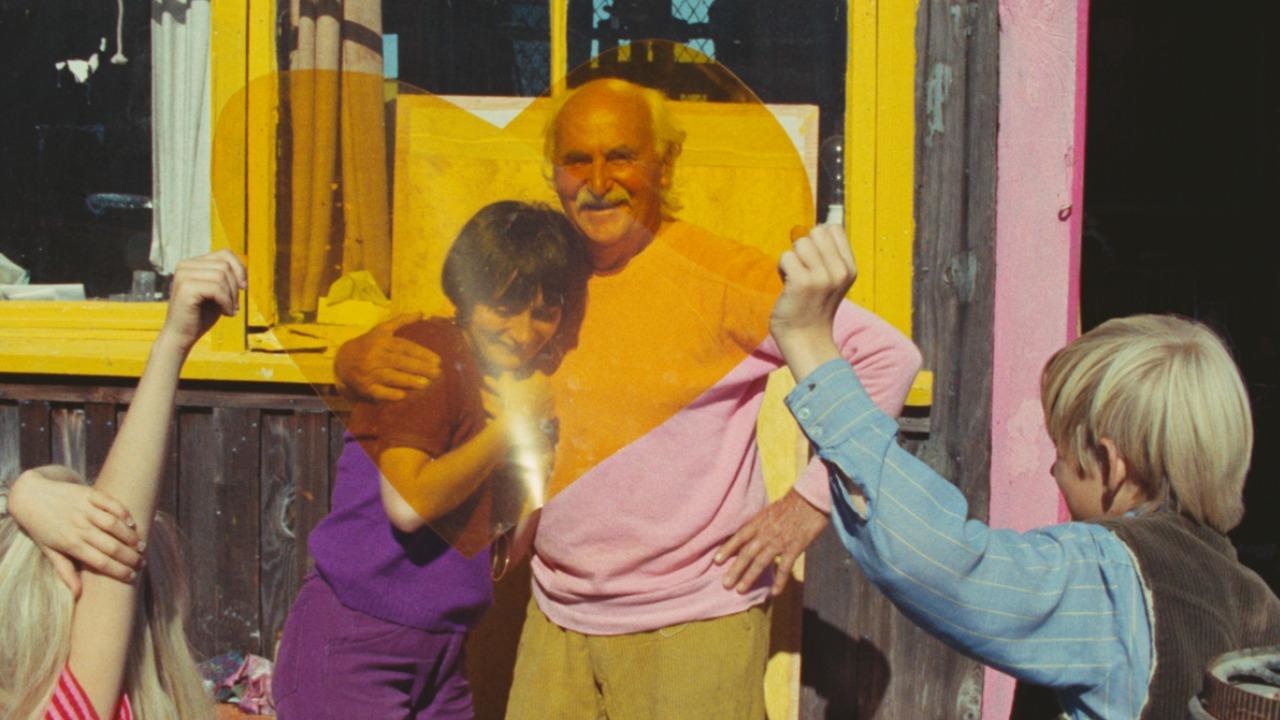

In 1967, I went to San Francisco to present Les Créatures. Tom Luddy, who was working for the Pacific Film Archive and was a left wing militant, told me: « —There’s a bloke named Varda in a ship in Sausalito. Does he belong to your family? — I don’t know, let’s see”. On a Thursday, I went there with Tom, and I fell into the arms of that Yanco, one of my father’s cousins. I was so shocked when I met him, even at first sight –he looked like an ideal father to me– so I had to film him. He spoke well about colours and his own paintings. He said: “Between the desire and the frame… there’s a slight grief, as a shadow that passes away”. He impressed me very much. We started around eleven o’clock, we shot during the whole Friday and Saturday; on Sunday, I filmed a bit in the morning, because his mates were there; sound was finished on Monday morning and that was it. I had to go back to Paris for editing and mixing Oncle Yanco for four weeks. Also I had to close the house, organise a short stay, because we were leaving for a year period at least. We gave plants away as presents, scheduled the trip, and Rosalie, a dog and me flew on December 24th to spend, along with Jacques and Uncle Yanco, our first Californian, sunny Christmas.

Making a film in Hollywood, is it a documentary or a fiction film? The question was valid both for me and for Shirley Clarke. She received several offers in Los Angeles, but they reached no agreement. Thus, she agreed with the idea of re-interpreting this situation which reminded our own situation. Lions Love is not an underground film, it is a film financed by someone who didn’t belong to any film studio. His name is Max Raab, a manufacturer in the clothing industry in Philadelphia, and he said to himself: “I’m going to invest my money in film making”. It seems that he had watched my films four or five times; when we met in a cafe he made up his mind in ten minutes. I said: “Would you like to read a part of it? I’ve got here ten pages”. He answered: “It’s not worth it, what you just told me sounds quite clear”. These things happen in America. Sex and politics. USA’s great two trends in 1967.

Three actors –Viva, Jim and Jerry live in a rented house in a Hollywood hill, halfway between their “stardom”, and their no less difficult maturity. On the one side: the three of them in bed at breakfast time. On the other: a TV channel broadcasts a story of national importance. The political assassination of Robert Kennedy reduced to a small image inside a box. It’s closer to a chronicle than a story, because the actors interpreted more or less their own roles. As soon as she arrived, Viva said she wanted to improvise, immediately. And so she did... She’s completely unique; she just reminded me the stars I liked, such as Arletty, Garbo, Lillian Gish… but without imitating them. The three of them have their hair style like a lion’s mane. They talk a lot, often at the same time. The film construction is rigorous: each situation and every sequence were envisaged, written; but since characters are placed in an adequate situation, I often recorded their reactions and monologues. I wanted the actors to perform without a script, interpreting themselves in a plausible situation. They used to rehearse in front of a tape recorder, saying everything that crossed their minds. I would keep two pages with their best material on the subject, which later they would read but just once, 24 hours before shooting.

I like filming real people. It’s not that I try to undervalue the work of the actors, nor their ability to invent a different reality, but nothing is so exciting to me as finding in real life the models and characters to film… or not. I love to see how they enter the scene by themselves, to listen how they speak, to observe their gestures. That’s how I learnt, after 20 years living in the same street, to better understand my shopkeeper neighbours by filming a documentary in 1975. I ordered a power line deployed from my house meter. The cable was 90 metres long. I decide shooting Daguerréotypes starting from that distance. I wouldn’t go beyond the reach of my cable. I’d find what to film in there, not farther.

The talent of a documentary maker is to make oneself forgotten. It’s just to lay one's cards on the table. It’s also telling people: I’m going to light up; I’m going to be there, but after that forget me. We start right there, where TV stops. They are the main subject. Not me. It wasn’t my intention to make a political film. On the contrary, I pursued a completely accessible approach. I tried to register their way of living, their gestures. That was because there is such a sort of gestures in human relations, inside small shops, and it’s there where I could find many fascinating things. A documentary work is not only technical and cinematographic. It lies in approaching others, listening to them and also being wit and make them talk, but placing them in a situation where everything runs properly.

I took advantage of a 14th of July (1976) to make them dance, for instance, since that day is the one we can pour into the streets. I told everyone in the neighbourhood to come and bring their chairs. As in the case of La Pointe Courte, I realised that the film, to my neighbours, was just a series of animated pictures on a screen, which said in a loud voice: “Have you seen Napoleon’s dog… Oh… Gilbert… You’re dishevelled”, etc. There was a change –just one– before and after Daguerréotypes. They had realised that filming was a true job. They had seen Nurith taking the 16 mm. camera on her back, they’d also seen us starting very early in the morning to light up the shops… Before, they thought I was a fibber, non-conformist artist. After, I turned out to be a worker.

Sylvie Genevoix and Michel Honorin requested me, like to some other female filmmakers, to shoot seven minutes on the subject “What is it to be a woman?”, for the F. comme Femmes magazine. I cut down the issue to “Our body, our sex”. With just seven minutes, it had to be done quickly but not grossly. Réponse de femmes was a ciné-tract. Thus, I demanded the possibility of talking about the body and showing it according to our way of exhibiting it. Negotiations with the management, sex in the forefront, yes, but… Eventually they cut the forefront takes before screening the film. It was not about talking on female condition, but rather discovering it from inside a woman, almost physically. How they react in view of what society claims to their bodies, how they sell themselves, abused. My symbol is a picture of a woman: half her body is covered; the other half is naked.

In Une chante, l’autre pas, the main subject is not love, with a capital L for Love… but female identity. The relationship of the two women with maternity (suffered with love, yet still suffered, or rejected, or desired, or praised, etc.). And their relation with work, with female solidarity. And then love, and love affairs, among the rest of feelings. It’s a look by a female author on the history of feminism in France, from 1962 to 1976, «turning around» two female figures, with different characters, tastes and social media. One of them has a dramatic, lonesome abortion, while the latter has a better one and is surrounded. Their paths are not parallel, they are just escapes. There are agreements in unison, like the female family or the final twilight. It is a limited subject. As a filmmaker, I wanted to mix my voice with the imaginary dialogue between the two girls, to speak about their friendship; it’s something certainly concerning to women, to us, who defend our capacity to agree. I didn’t mean to be the intrusive, omnipresent author-narrator … It’s just me in the film with them, between them. The vocal trio seemed therefore fair to me.

All my films are produced around contradiction-juxtaposition. Cléo: objective time/subjective time. Le Bonheur: sugar and poison. Lions Love: historical truth and lies (TV)/collective mythomania and truth (Hollywood). Nausicaa: history/mythology, the Greek people after de coup d’etatand the Greek gods, though this time it was also a mix, like in L’Une chante…, of fantasy and documentary. Nurith Aviv raised me a lot of questions, very moral ones: «Are you sure we have to go ahead with the Iran thing? We should cancel the trip…». I insisted. When we suddenly see evidence, what a funny pleasure. When all of the sudden I saw in Iran all those sex-minarets, all those nipple-domes, that sexuality in architecture spread all over sacred places where space is really sublime… In Plaisir d’amour en Iran I felt like using that look to indirectly reflect the voluptuousness of love by means of pure forms.

With every commissioned film I take advantage of reading again the poets or re-watching the films. I was offered to film the caryatids at the request of Terry Wehn-Damisch, who wanted to produce a series about arts, and which title would be Domino. In Greece, where the original-originals are? Too far, too expensive. In 35mm? Too expensive. We would shoot the Parisian Caryatids in 16mm. in Paris, and I would be able to read Baudelaire’s poems while caressing the stone dream-women with my camera. I was walking along Paris, I was reading, and the subject became richer by itself when I realised that most Parisian caryatids were dated around the 1860s. They started appearing in the buildings during this culturally prodigious decade, the same decade that saw Flaubert, Delacroix, Marx and his Das Kapital, Offenbach and his La Belle Hélène… and above them all, Baudelaire, who fascinates me. I could listen to his voice, his poems inhabit my ears. That’s how the association was established and the film took shape: the Caryatids at the time of Baudelaire’s last years.

At the beginning of 1984, in Avignon, I visited the magnificent buildings of the Saint-Louis hospice, where the far echoes of the fourth age voices -a sad sweetness- still waft through the air. It was there where Louis Bec had invented and assembled the exhibition named Le vivant et l’artificiel. There could be seen live llamas in the courtyard and stuffed bears in the corridors, abstract paintings and a turkey living in the kitchen. There were piles of plaster skulls in a room; in some others, there were artistic accumulations, stones on the floor, mould on the walls. When I was back to Paris, I called Louis Bec and Bernard Faivre d’Arcier to ask them permission to film at the exhibition, not to report it, but to draw inspiration from it. Permission granted. A few days later we went there to film. 7 p., cuis., s. de b. was filmed during a complete improvisation, in the absence of any reference points and without a safety net. I was only conditioned by those real heartbeats that I had felt visiting the place and the still-sweet presence of the elderly.

Winter was inspiring me, drawing landscapes instead of painting them. During the time we shot Sans toit ni loi, we could read a lot about the new poor in newspapers. People who live in the open during winter intrigue me. The image that persists is Mona within a landscape of vineyards dominated by two cypresses. I had been aware of them since a long time before: they were two guideposts in the field, near Montpellier, even before it was built a highway where lorries pass, day and night. The image of the mound with two cypresses, as if it were a grave ready for Mona was already in my mind when I asked Serge Rousseau, Sandrine’s agent, if I could meet the woman I admired in the incredible À nos amours, by Pialat. She was the only one I could think of for the unruly tramp. I explained Sandrine what was ahead for her in detail: a role without smiles which would be hard to live, the coldness required by the script and the rough conditions implied when shooting in the open countryside. I also told her I liked what we could imagine about her possibilities. Sacred daughter! She didn’t disappoint me. We admired how she stood against cold and tiredness. She impressed me. In fact, she has moved me more than once, particularly that day when she had to fall into that ditch from which she would not stand up again.

It was all about studying the effect caused by a character who doesn’t want to hear about the people representing the provincial France, closely tied to their traditions, such as their jobs, property, honesty, family, and in the end, their homeland. Thus, someone who refuses all that provoke reactions. Hence those refraction portraits, those multi-faceted mirrors. That kind of people define themselves when speaking of themselves. Wandering and dirtiness are subjects that fascinate me.

Actors, whether professional or not, are always more important than things in the background, that’s pretty clear. However, the staging is built up on so many elements to be controlled, while the light is changing, that sometimes becomes unpleasant. Sandrine was conscious of this continuous combat against the elements. Even if I had to murmur her something, to remind her some gestures to be done or how to drag her feet: She was there, always ready. She would grasp it all very quickly, so I didn't have to insist, and could take care of the lens, tracking shots and trucks.

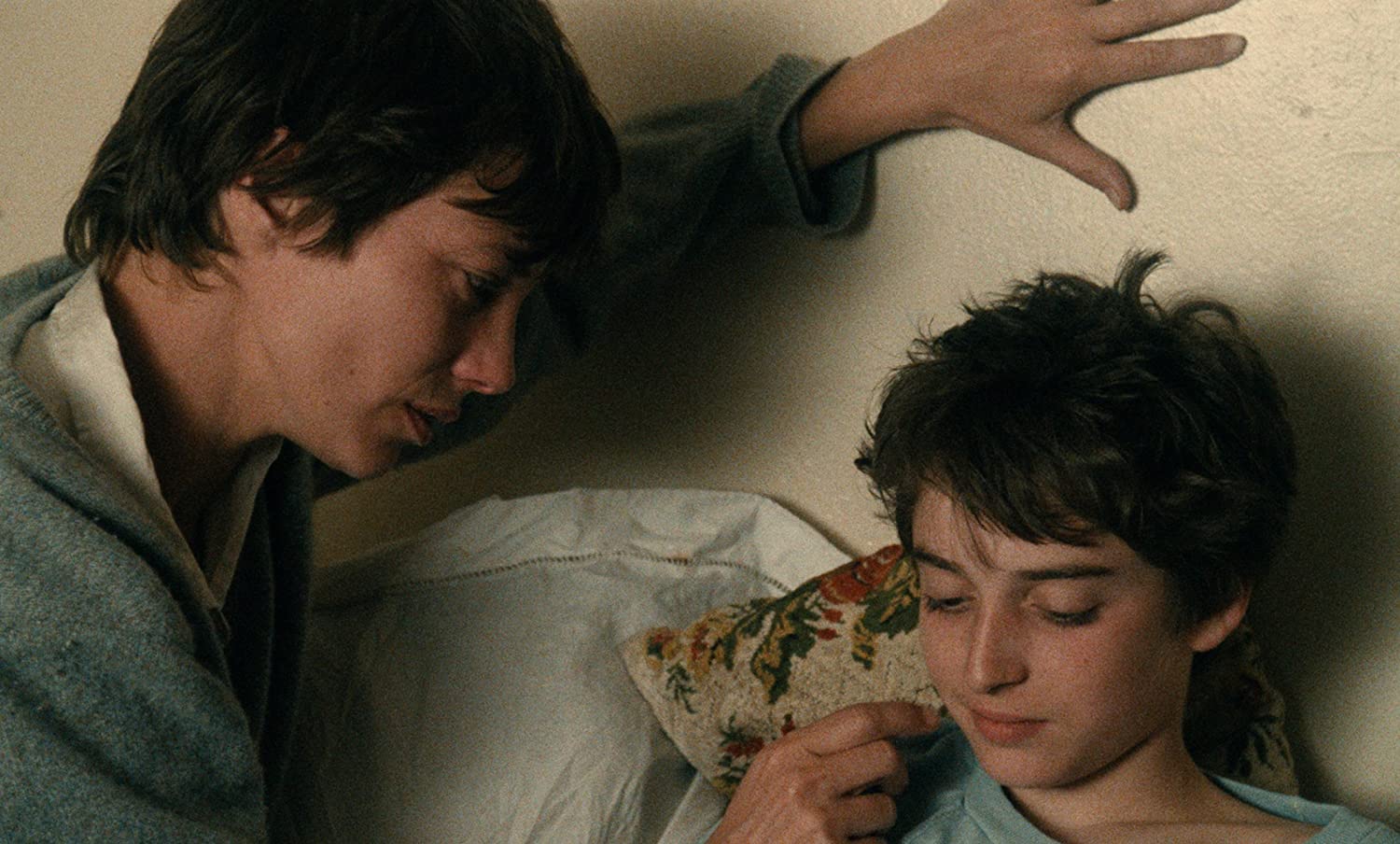

The texture of Kung-Fu-Master, a fiction film, is Jane’s reality, her family’s, and Mathieu’s reality. Jane was glad to film with her daughter. I was glad Mathieu was shooting this film with me. Later, Charlotte and Mathieu would change, they would own the trace of this passage in their lives. Jane and I had the hope that we would be able to intensively keep the memory of that time which wouldn’t last. Which is already past. That was 1986-1987. I observed children between 14 to 16 years old and raised me questions about the questions they were making. How to love? What to love? What are the gestures to be done between the permitted and the dangerous? I wanted the pre-adolescents party to be seen, and their jokes about the «condoms» (none of them used the word «prophylactic»). I heard how they laughed at the story or at the politics. In the film, they make fun of Hitler. Serious subjects for children were motorbikes and its accessories, and often, TV and all kinds of games.

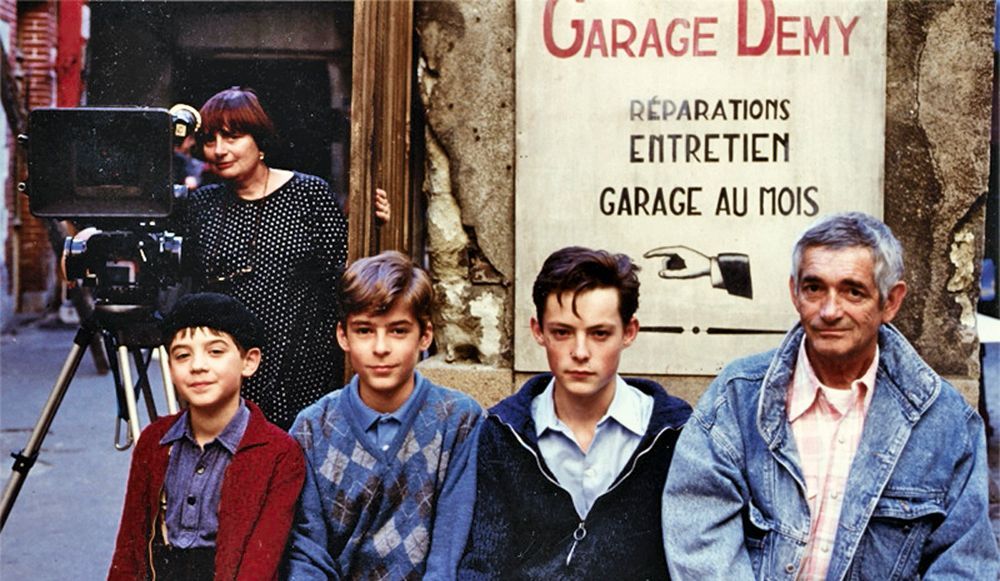

In 1990, I wanted to give some news of Jacques Demy. News on his work, which became gradually our work. Jacques was tired, and begun to speak about his childhood more often than normal. So I told him: «Write you memories». He started to write them. Every afternoon I had the right to my little portion of three, four or ten pages of memories. That’s how our rituals were in that time. Short hospital stays in between, and revelation in one fell swoop. What a beautiful script is being written. I told him: «Listen, we’ll make a film out of your memories». With great simplicity he said: «Ah, yes, it’s a terrific story».

Jacquot de Nantes tries to be a synthesis of three films to be done: first of all, the tale of Jacques’ childhood, after he had told me his written memories. The second film is a kind of study about the question of where does the filmmaker inspiration come from, and more precisely, why did Jacques Demy make his films. My own point of view is that his prettiest films, his most beautiful scenes, all come from that part of his childhood between being nine and ten years old. The third part of the film is very modest and it only takes a quite short period in Jacquot de Nantes. I wanted to film some Jacques close-ups, images of his skin, parts of his hands and face, as if they were a landscape we can visit. It positively seemed to me that it was impossible to film this far distant child I hadn’t meet without cinematically relate it with the present man.

Once I approached Jacques: «Do you like it like that? Does it resemble to this? Are those the gestures? And the words? What do you see? What do you feel about it? Please tell me». He answered: «I’m there». Those simple words made me really happy and confirmed that I was also there. I was travelling through the memories of another person, walking along with him. Reliving another age. I couldn’t help feeling perplexed -and I still feel like that- when the film is perceived as a homage to Jacques Demy –the disappeared, much-missed one– and not as the story of little Jacquot and his vocation. However, the true answer is much more intriguing, and I still wonder what kind of transference, without doubts, what kind of osmosis led me to film Jacques Demy’s life as if I had shared his childhood, or even better, as if that childhood would happen in the present time.

Rochefort inhabitants were not wrong when they decided to organise a great party on June the 5th, 1992, 25 years after the shooting and the anniversary day of Jacques birth. Invited as Agnès Demy, I wanted to shoot this unique event: a city celebrates a film with which it is identified. And I didn’t want to miss the opportunity to confront the people who lived it with their own memories, particularly the child extras that became adults. During the editing of Les Demoiselles ont eu 25 ans, the game consisted of mixing the images of the summer of 1966 and the ones of the summer of 1992. In 1966, I was present during a significant part of the shooting of Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, filming purely for pleasure. I liked to watch how a «musical» was done. I had plenty of time. I filmed at my own ease, moved around actors and technicians, holding a very big camera loaded with a double side film, made by amateurs. It was not an assignment, no promotion to be done, I was just gathering memories.

As for Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, which was in my mind four years before and took me one year to shoot, was seen by all foreigners; it was in the festivals, in cinematheques, in the museum of Nueva York... In fact, the petition came from the theatres, not from distributors. We planned to work with 15 copies. There was no method, we made it somewhat by chance. We raised a huge screen in Uzeste, in the middle of a meadow. There was an old church behind, which was highlighted in the semidarkness. People was mad, an article said there were 3,000 individuals. On the following day, we organised a debate with José Bové on the excess of consumption. He has raised the same problem everywhere. It is not a sustainable economy, nor a fair trade, but a society organised around cash, «the higher income» in mega-budget productions, in over consumption, in a super-waste. In Lussas, a young girl approached me and said: «I’ve got access granted to municipal cinemas in seven towns, four of them have 1,000 inhabitants and 400 inhabitants in the others. I’d like to screen your film during seven days, each day a different town. I can guarantee 200 tickets per week». The ADRC produced five new copies. That was how the film was screened at the Île-d’Aix for a day, at the Île d' Yeu for another one, and in different towns of Vendée, Gironde or Massif Central. During that time, big capital cities were awaiting for the copies. Which made me laugh a lot.

As for Les Plages d’Agnès, it is, above all, a filming exercise. I mean is not a memory or life exercise. My challenge was finding a shape to accommodate my desired tale. It’s a film inspired in cinema rather than in my own life. It was inspired to find a unique shape. And my inspiration comes from everywhere, which allows me to show two paintings, for instance. Filming paintings in a film work is a way of breaking moulds, breaking the limits, the frontier between fiction and documentary, between tale and imagination, between short encounters and feelings.

Something I like very much in Plages d’Agnès is having revisited my childhood house; I went there completely alone, because I think what was at stake were my memories. I got there, crossed the garden, went upstairs to my room, I asked myself where did my sister sleep and I met the train collector. I felt so interested that I turned into my documentary maker side. I made him speak, realising it would be much more fun for the audience to hear and see this man than getting to know where was the bed of my sister.

At the very end is the scene of my birthday. I’m sitting around 80 brooms I got as a present; I say a sentence which is the film key: «I remember while I’m alive». That means that the past forms part of the daily life. All past troubles, the memories that put me in a good mood, the flights, or desire, everything forms part of my present day, in the film I make today. I hope we find all those things in the film: the love, the loss, the desire, the joke, the children… Do we find it all?

***

Selection, translation, arrangement and management of texts:

Francisco Algarín Navarro, Alfonso Crespo and Clara Sanz

References:

"La grâce laïque. Entretien avec Agnès Varda", Jean-André Fieschi, Claude Ollier, Cahiers du cinéma, nº 165, April 1965; "Entretien avec Agnés Varda", Jean Narboni, Serge Toubiana, Dominique Villain, Cahiers du cinéma, n° 276, May 1977; PRESS ACCREDITATION French Dossier of Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, Ciné-Tamaris, 2000; “Entretien avec Agnès Varda à propos du film Les Plages d’Agnès”, Marcel Jean, 24 images, March 2009; Varda par Agnès, Agnès Varda, Claudine Paquot (Ed.), Cahiers du cinéma, Paris, 1994/ 2005, “Le bel été de la Glaneuse”, Elisabeth Lequeret, Cahiers du cinéma, n° 550, October 2000; “Entretien. Agnès Varda de A à Z", Raymond Bellour, Jean Michaud, Cinéma 61, n° 60, October 1961; “Vers le visage de Jacques”, Agnès Varda, Cahiers du cinéma, nº 438, December 1990; "Agnès Varda : Expérience américaine (Entretien)", Bernard Trémège, Jeune Cinéma, n° 52, February 1971; “Rencontre avec Agnès Varda”, Rochelle Festival, 2012.

We are very grateful to Miguel García and Basem Al Bacha.