In his day Carl Gustav Jung considered the existence of a collective unconscious. A kind of underground root that connects us, a common base of which we are unaware. A theory that has a magical aspect, but at which Jung arrived through scientific methods. We start talking about Jung, not only because he is among the favourite readings of Ildikó Enyedi, but because in some way that strange mixture of psychology and spirituality connects with the films by the Hungarian director, which although they present supernatural events go beyond mysticism and fantasy to occupy a place of their own thanks to the peculiar use she makes of cinema’s tools. Her universe sets out a natural relationship between apparently opposing elements, in a natural flow: like life and death, which although they may seem like two separate poles, are indissolubly united. This is how in her cinema magic and philosophy, self-determination and fate, light and shade, conscious reality and dreams, body and spirit go hand in hand. Dualities that surrender before the naturalness with which she represents the unimaginable before our eyes.

Her vision began to take shape between the end of the 70s and start of the 80s, years when she belonged to the underground artistic collective Indigo, where she began her journey through conceptual art and performance. Later she worked in the Béla Balázs Studio, the only independent film studio in pre-1989 Eastern Europe. During this first stage she made more experimental films, between documentary and fiction, in which she analysed the relationship between the person and the filming, and about the psychological (but also social) tension that a camera can unleash. That period also give rise her first feature film Mole (1987), a work about the body and the conscience based on La invención de Morel by Bioy Casares: a story about a ghostly world, which Enyedi identified with the ghostly world which cinema is, that parallel reality of projected shadows. A character parachutes into a place in the middle of nature. Here it is the camera’s point of view that plants that idea that something is happening under the visible surface of things. The spy seems to be spied on, certain angles seem to tell us, among the vegetation a certain perspective on the bend in the road, the choice of a hand held camera at a certain moment. The whispering voiceover of the parachutist adds a layer of strangeness in that same direction.

After Mole, Enyedi made My XX Century, in which a pair of identical female twins separated in childhood represent the contradictions of the XX century (one, a fortune-hunting libertine, the other a feminist and fiery anarchist) with which she won the Caméra d’Or at Cannes. A delicious film, full of digressions and unexpected paths, in which she extracts the magic of the arrival of the XX century from scientific inventions such as electricity: both in the start of the film, with a nighttime parade for Edison’s arrival in Paris, and in the New York dance spectacle with lights, they envelop the story with a certain significance of the change of century. The unconscious collective is manifested some way in the Orient Express stopped on New Year’s Eve 1899: the seconds before the chimes, a journey through the impalpable moment of silence and expectation on the passengers’ faces spreads an invisible net that penetrates all of humanity. Likewise, sequences like that in which some monkeys observe a human as if he were a strange specimen reverses the perspective, showing the multiplicity of points of view on reality. The presence of the stars (in contrast to lightbulbs) as a division between sequences also give the overall a halo that makes us think of a cosmic, bigger than life, vision.

After My XX Century, Enyedi presented her successive films, Magic Hunter and Tamás and Juli in the Official Section of the Venice Festival in the years 1995 and 1997 respectively. In 1999 she showed Simon the Magician at Locarno, winning the Special Jury Prize. With, at first sight, a more absurd approach than My XX Century (a Hungarian magician who comes to Paris to help the police solve a murder), this film is certainly more sober in its forms. Péter Andorai (who played Edison in My XX Century) brings from the outset a calm presence, which fits with Enyedi’s delicate ways of demonstrating his magic gifts. The sequence in which he resolves the crime, the magician has a siesta in a large room with large windows; a ray of light on a plant is enough, in a serene editing which seems to savour every shot, holding its breath, for us to know that the miracle has happened. A gaze that rests on random objects and people with sufficient insistence to give them an extraordinary importance.

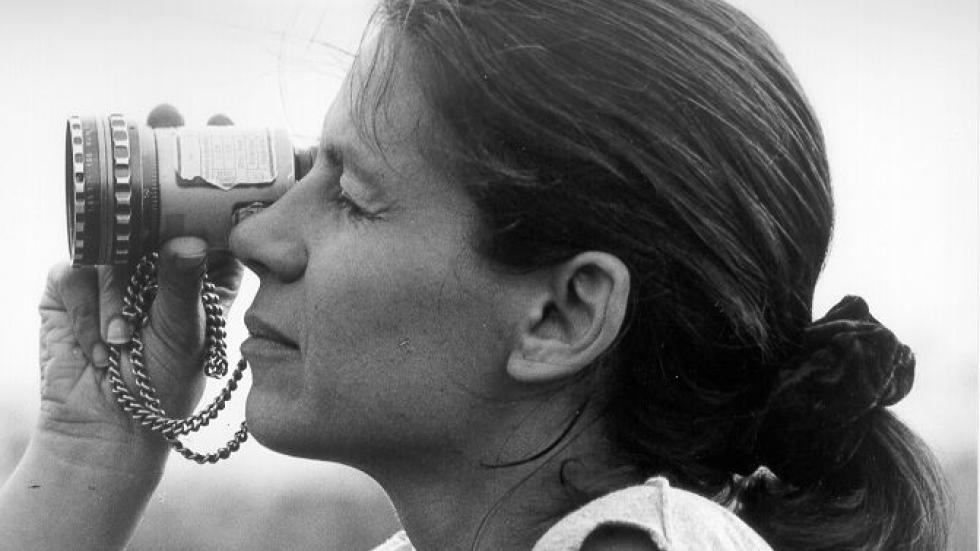

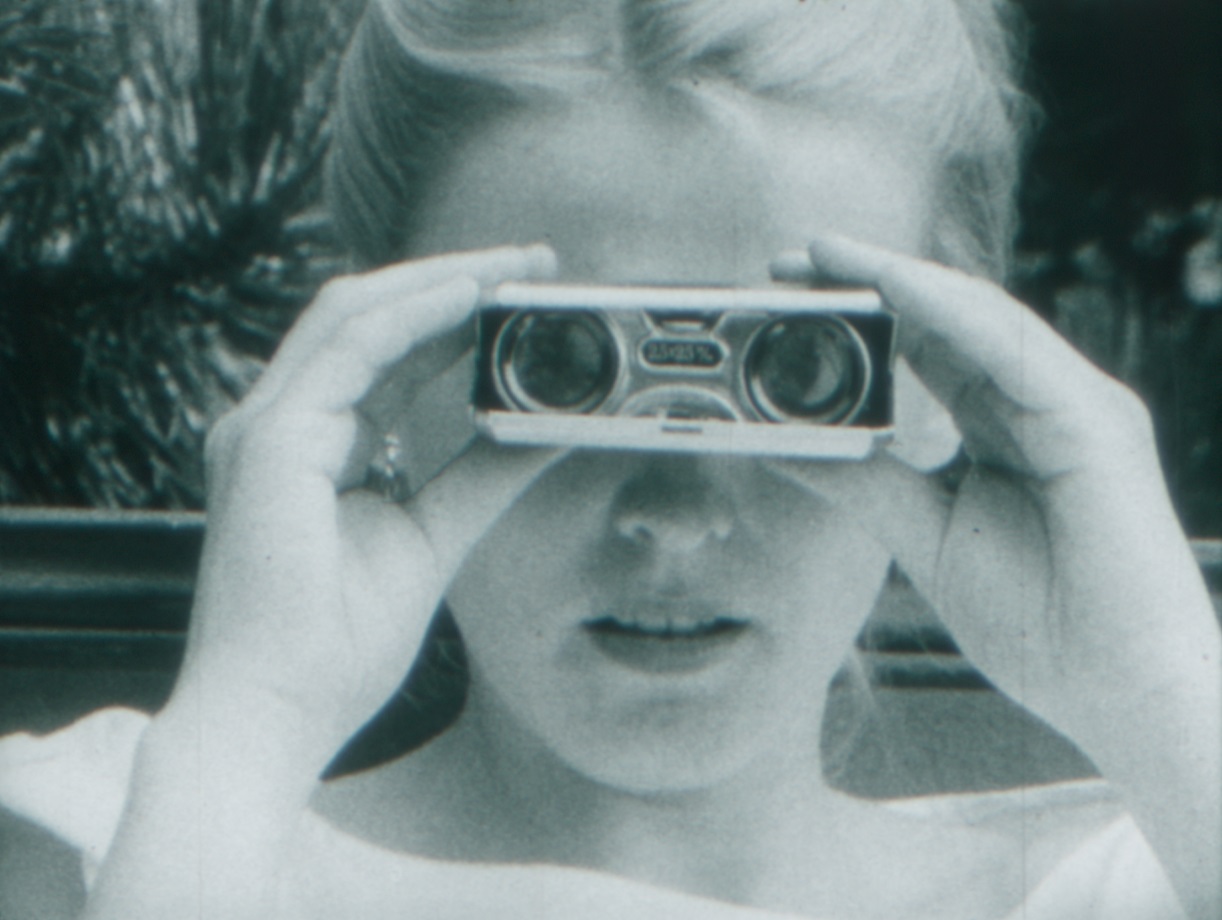

In this group of films there is an allusion to cinema, when Enyedi makes it clear in different ways that what we are seeing is mediated by a device and is a reflection of reality: for example, the woman’s binoculars in Mole, the start of Simon the Magician, which we see through a tumultuous television sequence, or the arrival of cinema in My XX Century, paired with the game of mirrors in its final sequence.

Eighteen years separate Simon the Magician from On Body and Soul. Sufficient time for her name to sound familiar to many, especially when she won no less than the Silver Bear at Berlin (and also the Fipresci award and the Ecumenical award at that same festival), obtained four nominations for the European Film Award (winning Best Actress for Alexandra Borbély) and she was nominated for the Oscar for Best Film in a Foreign Language, along with a long list of awards at festivals around the world. In the films about which we have talked until now the idea of lovers destined to meet through the most capricious of coincidences is present: the impossible meeting between the parachutist and the lady in Mole; the cosmopolitan gentleman who falls in love with one of the twins in My XX Century, whom he confuses in a chance encounter; the magician Simon who, as soon as he sets foot in Paris, meets a young woman who without knowing it is his destiny. Except that here the love story is the heart of the film, and the “magic” is found inside the couple that concern us: a robotically timid young woman and an older man with a lifeless arm. Each night they meet in their dreams in the form of deer. Their shared subconscious is here an icy forest. By day, they meet in that place between life and death that is the abattoir where they work. The slow, complicated steps for the “spiritual” encounter to become a physical encounter are modulated throughout the film with a calm editing rhythm, an expressive work with the actors’ looks, and framings that are elaborated almost to the millimetre. There is no ingenuity, however, in Enyedi’s gaze. She knows that romantic love is a terrain strewn with mines once the ideal clashes with the real. Two solitudes cross with their delicate obsessions and specificities which the director shows without sweetening them.

In addition to the dualities with which she works and her way of looking with amazement at reality and with naturalness at the supernatural, there is a great sense of humour that runs through all her work. Directly satirical elements in My XX Century (that discourse to the feminists about the reasons for the inferiority of women), the ironic personality of Simon the magician (that conversation between Simon and the young woman, in which she appeals to him and he answers yes or no at random, not understanding a word of French), or the pathologically comic edges of the protagonist in On Body and Soul: from when she goes to buy romantic music to when she stops the bleeding on her arms with insulating tape.

Enyedi’s filmography shows, as we see, a singular coherence that materialises in a creative universe of great richness: that is why a retrospective of her work is necessary and clarifying, and reveals the very particular aspects of her gaze. But her work mustn’t shine only for recent successes, but for its solidity and its overall force. Enyedi has understood better than anyone that the important things happen on another plane, that isn’t perceptible at first sight, but that runs like an underground current. “One does not become enlightened by imagining light but by making the darkness conscious… what is not made conscious manifests itself in our lives as fate…” wrote Jung, and certainly Enyedi’s films seems to operate precisely in that space, in which cinema is presented as a very useful tool for making the ineffable manifest itself.