In the same way that ignorance of the law excuses no one from its compliance, ignorance of a film tradition excuses no one from participating in many of its fundaments. Spanish cinema is full of red threads and underground currents which link films that are apparently far removed and distant. Some of these threads are obvious, such as costumbrismo or farcical humour, but it is much more unusual to realise that themes such as the appearance of a stranger, or generic hybridizations, such as the mixture of melodrama and film noir, feed Spanish films of all generations. Magic anthropology, if you’ll forgive the oxymoron which often seems a redundancy, is one of those threads. We have legendary films such as Las Hurdes (Luis Buñuel, 1933), La ruta del Quijote (Ramón Biadiu, 1934) Galicia (Carlos Velo, 1936) or Boda en Castilla (Manuel García Viñolas, 1941). These kinds of films, common during the Republic, with a certain regenerationist intention and very political, disappeared with Francoism, when popular culture was diluted into a folklore that was easily manipulated, but they reappeared in the last years of Francoism.

For that reason, in the mid-70s, when revolutionary movements started to disappear or show clear signs of their failure, many European filmmakers opted for changing strategy. Instead of continuing to testify to liberation struggles around the world, they decided to look at their own surroundings, at the traditions and popular mythology of their own countries, as bastions of purity uncontaminated by power. Since then, many films have sprung from the mise-en scène of those collective rituals composed of indigenous mythology and folklore, with a purer, even naïve, look at the indigenous, non-transferable collective imagination of each country. Only in that way could cinema manage to take root with the different national and popular cultures.

These films broke with the distinction between a recorded reality and a staged reality to go more deeply into the concept of mythology and ceremony. In this way, scouring through ancestral practices, on the one hand they found a part of the culture not corrupted by industrialisation while on the other they questioned the nature of cinema itself, by breaking with the line dividing genres and languages. This focus on the rituals which are in all cultures also had a critical intention: only by clearly perceiving the atavisms and the taboos which have been imposed on us could we get rid of them. This cinema appears before us as an attempt to understand History by telling the thousand stories that make up a People, who find in those stories and in that collective imagination their closest, most coherent unity. The omnipresence of the people (as identity, as character, as territory) ends up becoming a universal reflection on the fate of all that which progress abandons by the wayside, and the assertion of which became the last hope of the revolution. The panorama of films which we present emphasises these ideas, the search for alternatives between fascination and criticism to a mediocre, tamed cinema that transformed identifying signs into clichés.

The season opens with Visión fantástica, by Eugène Deslaw, a member of the historic avant garde of the 20s (director of Montparnasse, 1929), who, using images belonging to NO-DO, which showed folk traditions alleging that there was Spain’s true soul, many times with view to tourism, carried out an experiment using the Negavision method, a succession of images in negative or solarized, which offer a political counter-reading of those images. Walsed (2014) a short film by Alberte Pagán, is a cinematic study of Visión fantástica, in which Pagan shows in positive the images which Deslaw had used in negative, clearly showing the propagandist message which Deslaw had tried to make invisible.

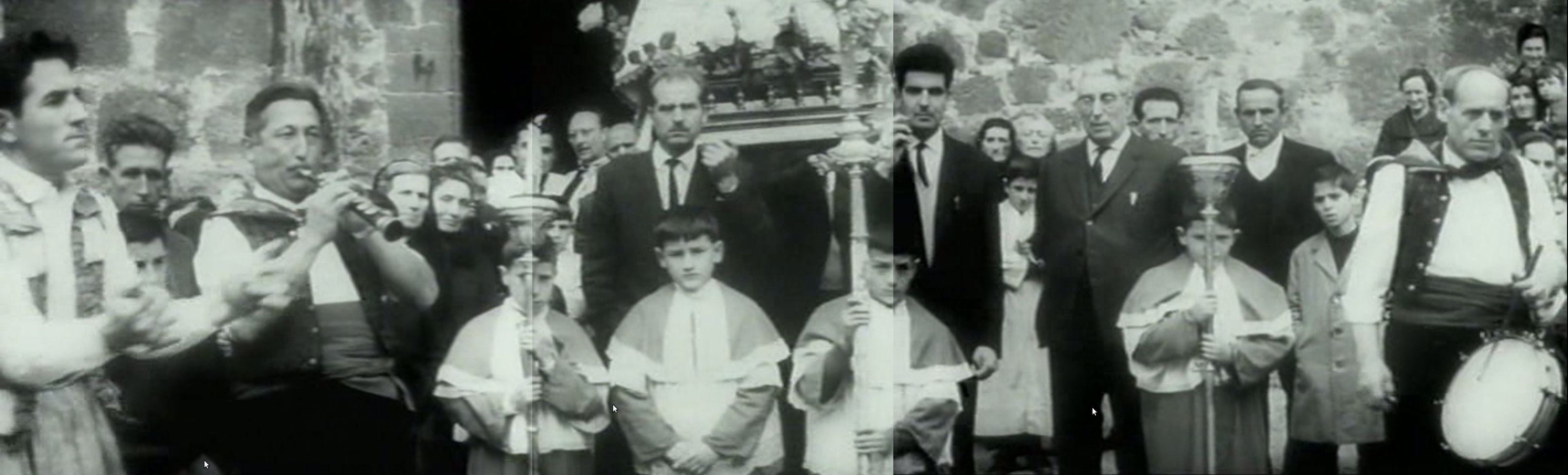

Lejos de los árboles (Jacinto Esteva, 1973) is the touchstone of all these considerations. Few films in the history of European cinema have shown as this one does that very often cultural traditions can’t be a source of pride, because they arise from a sociocultural backwardness that leads above all to cruelty. In this film, Esteva aims to make an anthropological analysis of Spain, showing that our essence is in reality a celebration of death, and that all the rites are based either on cruelty or on danger. This chronicle of deepest Spain connects totally with the idea of black Spain that has become so widespread. But the film contains an enormous contradiction: and it is that the denunciation of the backwardness or the primitiveness of our traditions is told with a great fascination: the director is fascinated and can’t stop looking. Along with this, we are showing Rapa das bestas (2017), by Jaione Camborda, who picks up a motif from Esteva’s film, making it timeless: her filming on Super 8 shows a time that has stood still, an eternal return to a tradition that we don’t understand and that we can only contemplate with amazed eyes.

The feature film La umbría (1975) shot on 16mm by the painter José Dámaso in his town of Algaete, in Gran Canaria, seems to us today like the precedent of the tropical gothic films by the Grupo de Cali. What begins like a 19th century melodramatic novel (it’s based on a play by Alonso Quesada inscribed in post-modernism) ends up being the chronicle of an atavistic enclosure, of the impossibility of escape, as cannot be otherwise on an island. In contrast with the large house, the decadence of those who live in it, in contrast with wine, blood, in contrast with the exuberant vegetation, the arid volcanic land. This film brings into play the collective imagination of an island, of a culture, formed from dangerous contrasts and where the horizon only brings the presence of a metaphorical skull. Montañas ardientes que vomitan fuego (2016) by Helena Girón and Samuel Delgado show you the same labyrinth, neighbouring mountains, without time, uncoordinated, where you can’t believe in the end of the world, because the end of the world is what surrounds you.

Axut (Jose María Zabala, 1975) is possibly the strangest film in the history of Spanish cinema, an island impossible to relate with any film before or after. Through the mixture of a Basque imagination (the mountains, the farmhouse, the French captain) and an imagination extracted from Hollywood cinema (the tough guy, the cowboy, the thief with the striped shirt) it tells us a parable of the loss of the Basque identity, which ends with a torture scene, eloquent in its insinuation of who is being tortured. And yet, this “metaphysical circus” as its director defined it, is a light hearted, entirely free film, inheritor of home moves and underground cinema, with a sound track (Jose Mari Zabala was an experimental musician) that weaves together everything from children’s songs to industrial sounds, the work of a true craftsman. Axut is a film that never wears out, and that shows us its apparent complexity with a plausible, friendly simplicity. Having viewed Axut, the pair of filmmakers formed by Ander Parody and Pablo Maravi make a re-reading that links with Zabala’s imagination, updating it to our day but also anchoring it in the remotest past.

The final session will show Insular (1971), a true rarity which Ramón Masats managed to make for TVE, perhaps the strangest work that Spanish television has ever produced. The credits explain that the work consists of “Six themes by Luis de Pablo/ visualised by Ramón Masats”. That is, a priori this film is the illustration of the music by the composer, the greatest figure in Spanish avant garde music. Using anamorphic lenses which disfigure the landscape, the filmmaker shows the landscape of Lanzarote, syncopated to the rhythm of an unrhythmical music, using the recourse of elements from avant garde cinema, but also from anthropological and even didactic cinema. Los montes (1981) by Chema Martín Sarmiento, tells us an apparently simple story: after the death of the last man in the village, the women who survive him gather together for his wake, and drink orujo and tell legendary stories that were told to them at some time. It seems like a film about the end of an era, that of mud houses, but really it shows us those women as inhabitants of the time of stories, of narratives, a time without beginning or end, where magic, friendship, serenity and losing the fear of death are all possible. To accompany these two pieces, we have El becerro pintado (2017) by David Pantaleón, a filmmaker who, from recreations of lost or forgotten rituals, again shows us the theatricality of popular culture.

With this season, the Seville Festival aims not only to reflect on our cultural heritage and propose a reading that is both critical and captivated by our cultural rites, but also to exhume from oblivion a series of titles very often more quoted than seen, so as to bring about the creation of other possible genealogies of Spanish cinema.