Somewhere between art and science, between fiction and reality, between Ukraine and the old USSR, the life and professional career of Ukrainian director Sergei Loznitsa (Baranovichi, 1964) is unconventional. A graduate in applied mathematics, he worked as a scientist at the Institute of Cybernetics in Kiev. Much of his cinema has dealt with the traumas of the inhabitants of the USSR and its political changes. The documentary, and its multiple forms, has been his usual tool since 1996. Since 2010, with 'My Joy', he has alternated reality and fiction.

An old acquaintance of the SEFF, in 2018 he won the Golden Giraldillo with 'Donbass', the same year that he presented two other films, 'Victory Day' and 'The Trial', perhaps unique in the history of the festival. And in 2019 he brought to the event 'State Funeral', another exploration into the historical memory. Dozens of international awards (including the FIPRESCI at Cannes 2012 for 'In the Mist', or the director's award at Un Certain Régard at Cannes 2018 for 'Donbass') endorse his prolific work.

This year he returns to Seville to present 'Babi Yar. Context' in The New Waves Non-Fiction, a section he already won in 2015 with 'The Event'. Here, Loznitsa maintains the creative coherence that often leads him to look at the past, to doubt the official versions, and to prevent disasters from repeating themselves in the future. Babi Yar. Context is about one of the worst massacres of Nazi barbarism, which happened very close to where he was born: more than 30,000 Jews murdered in two days, in the midst of the German invasion of Ukraine. Loznitsa works with images from German, Russian and Ukrainian archives, many of them recovered from private collections, and accomplished restoration work. Presented at the Cannes Film Festival, 'Babi Yar. Context' won a Golden Eye Special Mention.

Babi Yar. Context, by Sergei Loznitsa

We outline Sergei Loznitsa's approach to filmmaking through a number of reflections gathered from various interviews.

1) Documentary and fiction

"Every time I make a fiction film I want to get as close as possible to the limit, to the frontier, between fiction and documentary. On the other hand, when I make documentaries I go the opposite way, I get closer to fiction. I believe that one influences the other, and vice versa. I intend to continue in both genres”.

2) Manipulated reality

"It is difficult to think to what extent what is shown in a documentary is, in fact, a documentary. On the one hand, each separate shot reflects what it contains, what exists. But when we start editing, we start to change the meaning of that shot. It's not the same to place it at the beginning or at the end. In each of these places, the same scene has a different meaning. We can merge, in comparison, two different shots: from their union we obtain a third sense. When we construct a film, in one way or another an illusion is obtained which does not reflect the same reality of each separate shot. It doesn't matter if you shoot it as cinema verité. What we get at the end is not a documentary, it is only our imagination about that image we saw at some point. All the ethical questions are on another level. Ethics is a question of the relationship between people but what we have in cinema is a relationship between nuances”.

3) Learning from the past

"I consider it my duty to look back, and therefore to look to the future. Russian history is a copy and paste. It keeps repeating itself endlessly. Hell does not appear when horrible things happen, but when those things happen again and again. It is very difficult to change the mentality of a whole nation. And it is very easy to manipulate people who do not remember their own history. The big question is how to educate people who don't want to be educated".

4) Russia yesterday

"I grew up in a country where history was unknown. They rewrote the facts, created a Soviet mythology and still we don't know what the history actually was. After the Revolution, in the years after 1917, there was so much bloodshed that we still feel the effects today. They killed the royal family, the aristocracy and the military elite. They killed, exterminated and sent into exile the entire intellectual class, writers, teachers, philosophers. They exterminated the clergy. There was famine, then the restructuring of the agricultural sector and its collectivisation. Another change by force. The Second World War also brought with it the great destruction of rural villages from which the countryside never recovered. After the war, there was another famine that killed some 10 million people. If we take a look at the history of Russia, it is tragic".

5) Russia today

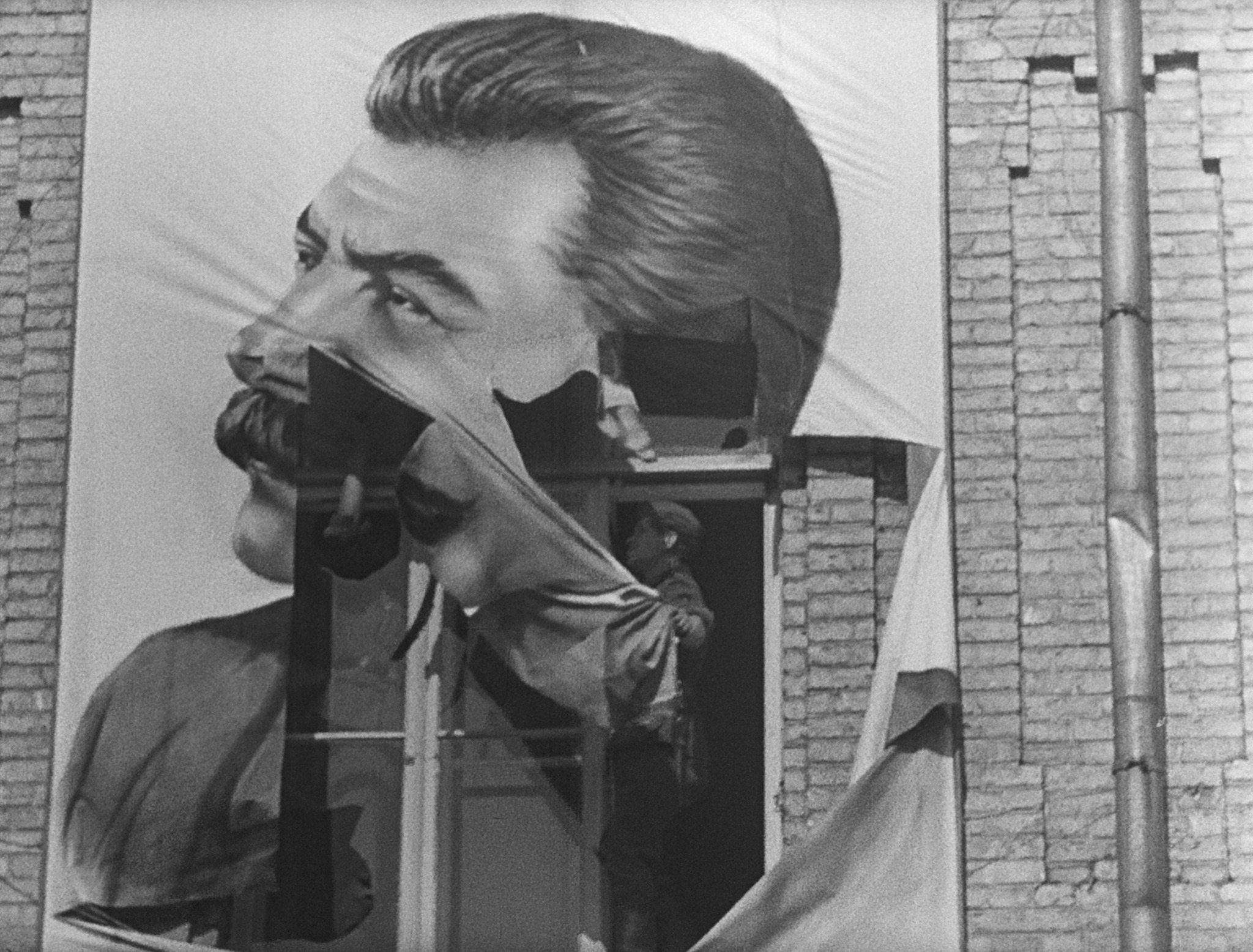

"I have lived in a country with an unpredictable past and, even now, Russia is quite unpredictable. It's impossible not to remember what happened in the Soviet era. But now they are trying to recreate a Soviet illusion. In contemporary Russia, Stalin is once again becoming a great national hero. It is paradoxical that the greatest murderer of the 20th century, the tyrant who killed and tortured millions of his compatriots and brought misery to millions of citizens can be considered a popular leader. It is as if Hitler is currently revered as a hero in Germany, an aberration. That means that people did not do their job well: historians, filmmakers, writers and politicians. There are so many untried crimes of the past.... We still need our own Nuremberg trials. The KGB and secret services tortured and killed millions of people, but these institutions have never been prosecuted either. And now it is clear that Putin is a product of Stalinism, even if the manners have changed".

6) Culture in Russia

"The problem is very serious. Culture can die out, die. For any strategy to work you need time, and we don't have it, because of the speed of disintegration, which is getting faster and faster. I have the impression that those who have the capacity to think are gone. The audience in the 1980s used to be critical. Today it is not possible. The mentality has been transformed. Senior professionals have been brainwashed. They are asleep. And the only thing that can save society is education. It is necessary, because it can give people an understanding of what is going on, without it... it's like driving a car with your eyes closed. I fear that people will slowly become infantilised, and will not be ready to take responsibility. And if we keep the same "democratic" elections, it's easy for an idiot to become president".

7) Politics and ideology

"It is impossible to make apolitical films, yet filmmakers are not dangerous on the basis of their ideology. People who don't think are dangerous. There are people who produce propaganda, of course. No one admits to being responsible for that propaganda: neither who pays for it, nor who makes it, nor who consumes it. But everyone is responsible: some for doing it and others for accepting it and opening up the possibility of being deceived”.

8) The spectator

"I wouldn't say that the aim of my films is to provoke something in the viewer, that's not the term I would use, as it has negative connotations. Rather, I want my films to urge viewers to move towards self-knowledge, self-awareness and to be aware of certain important things that they have never considered before. This is of the utmost importance to me”.

9) Influences

"We don't always know what influences us. There is a certain inertia in our perception of the world and we often don't understand the significance of an event until a long time has passed. So we can't always assess what influences us, but obviously there are directors and films that left their mark on my formation: Buñuel, Bresson, Hitchcock, Wiene, Murnau, Dreyer... There are films that one must watch in life, the rest are mere projections, reflections".

* Statements taken from interviews published in Film Comment, The Guardian, Photogénie, 24fpsverite, Huffpost, El Ángel Exterminador, El País, El Periódico, Clarín.