“The delirium of the poor is the generator of events, the source of history; a throng of feverish beings who want another world, here and now. It is they who inspire utopias, it is for them that utopias are written.” We start with this quote (whose author we will reveal later on) to talk about this new section, Endless Revolutions. A phrase that works in two directions in this selection which aims to gather proposals whose courage verges on the suicidal: the authors that we show here are those “feverish beings who want another world, here and now”, except that they do not inspire utopias but rather write them, film them and proclaim them. Because a revolution is a gale of change that is driven precisely by the collective vision of a kind of utopia to be achieved, for which to fight. And it is precisely the filmmakers who remain in that revolutionary, visionary state, who aspire to what is loftiest and most utopian, whom we want to summon here. Rebels with a young soul, those who always go a step further.

A VIOLENT DESIRE FOR JOY, by Clément Schneider, (with one of the titles most evocative of the spirit we are seeking) begins in the French revolution, but far from the clamour in Paris. With a clean look and clear spirit, Schneider transports us to the internal revolution of a young nun infected by the best of the revolutionary ideas, but far from its violence. With formal and aesthetic bareness (he barely needs a handful of actors, a timeless location and a few pieces of wardrobe and props) Schneider gives his film an eternally young air that links with the cinema of Rohmer and Eugène Green in that internal revolt of the character who ends up embracing the revolution also symbolically in the form of carnal love.

Another piece full of symbolism is ENDLESS TAIL, by Željka Suková. Specifically, the conflict between the sacred and the profane is what comes into play, in a piece that is capable of constructing other worlds (utopias) through the typical, nontransferable tools of cinema: the editing. Using all kinds of images and sounds, in an explosive collage, Suková is capable of conjuring up a world from an eye at a keyhole, of transforming a door in the middle of a field into a gateway between dimensions. The freshness and effervescence of the new Czech wave is revived in the work of this Croatian visual artist, in a timeless look laden with modernity and future.

There is also in Endless Revolutions another kind of more silent revolts, which have more to do with the personal and the intimate. Although Dídio Pestana’s register in SOBRE TUDO SOBRE NADA may have a nostalgic vein because of the use of Super 8, a photochemical format that is noticeable not only for its texture or for the warmth of its colours, but for the way in which the duration of the cartridges conditions the filming, it is clear that that what it ends up condensing is a clearly contemporary way of feeling. This collection of glimpses (in the style of Mekas or Menken) gathered over the course of eight years constructs in some way an impossible place, an emotional utopia of a life conditioned by the continuous mobility of a globalised European youth with a fragmented sense of belonging. On the other hand, Ilan Serruya needs to arrange that necessary father son encounter on the island that gives the title to his film, REUNIÓN. A powerful, breathtaking landscape frames Serruya’s look (patient, keeping a sensitive distance): a volcanic land that under an apparent calm hides burning tides, like the “peaceful” encounters between Serruya and his father, on a journey full of emotional suspense to that place of impossible communication, coveted utopian ideal. The ideal which María Antón looks at in <3 is flourishing: it is the view of adolescents on love and relationships, that shapes a luminous, radically free future for amorous relationships. One day, from morning to night, in Madrid’s Retiro park, in a kind of Comizi d’Amore of young people today, is not only an accurate survey of the unprejudiced look at the ways of loving that lie ahead, but also an atmospheric and sensorial experience that ends up sinking its roots in the unreality of night, of life and of the search for ceaseless pleasure, this time mediated by cell phones, in a reality that is no less authentic because of its virtuality.

Of course, in this bunch of utopias there must be the unlimited daring of pieces like M, by Anna Eriksson and HAPPY LAMENTO, by Alexander Kluge (featuring Khavn de la Cruz). M, for example, refuses to build a sequential or linear story, in a series of variations about the figure of Marilyn Monroe (interpreted by Eriksson) and about the relationship between sexual desire and death. Something that also comes through in the revulsive images of the film, which penetrate the senses varying between the stimulating and the disagreeable, generating a unique, unpredictable experience. Recurrence to the collective imagination seen through a deforming mirror (in a tone at times close to that of Lynch) increases the power of a film that dissociates itself from any existing label or classification. There is not enough space to start talking about the cosmos built by Happy Lamento, in a reflection of the lucid, multilateral and clairvoyant thinking of Alexander Kluge, and specifically of the thinking about the image (although he says that his film is eminently musical). This collage about electric light, the circus and the song “Blue Moon”, is mingled with images of the Philippine Khavn de la Cruz, in a strident, delirious dystopia whose backdrop is a rubbish dump, in a war between fierce gangs of children, The Warriors of the end of the world AKA the north of Manila. Kluge diverges from the path of lineal editing by splitting the screen in three with images that interact generating a torrent of ideas and associations. So we see that being a veteran (Kluge is one of the fathers of the New German Cinema, and has been active for over fifty years) has nothing to do with the rebelliousness of an incombustible spirit.

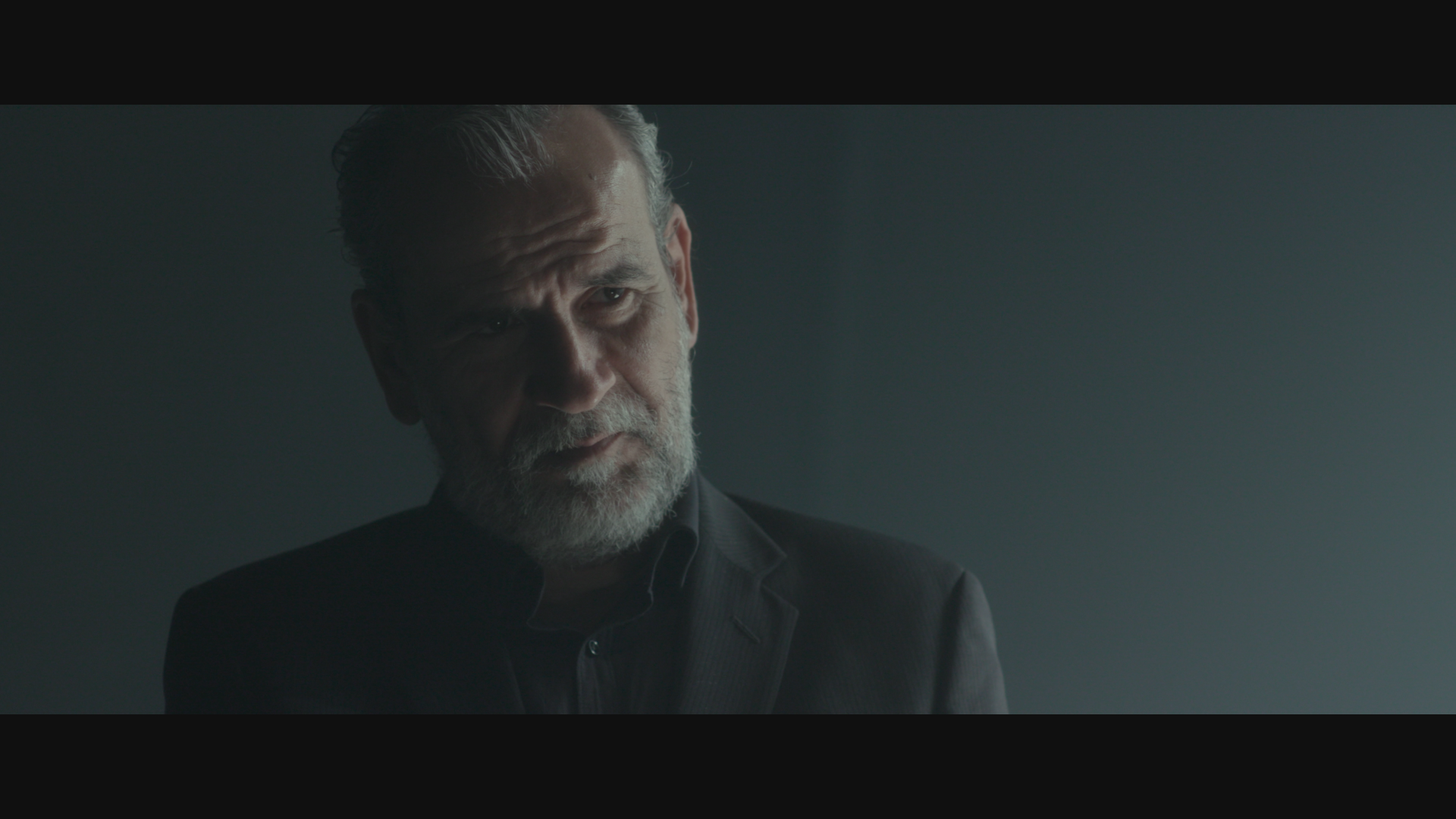

But utopia is not only in the subjects or the forms: the ways of working are also an active construction of an ideal here and now. La Cicatriz /La Bañera Roja, can be considered in some way as a utopia in the midst of the audiovisual industry. From there Pablo Llorca produces and directs his films, which arrive year by year from his prolific mind. EL VIAJE A KIOTO also rebels through its multilateral look at the world of art and the fleeting nature of success. In a more comical look than ever, Llorca builds a questioning farce of the marriage between art and market, a clear criticism that calls for a different world. On the other hand, starting from avant garde theatre, EL REY, by Alberto San Juan and Valentín Álvarez, is clearly militant in its forms and objectives. Around the figure of the king emeritus of Spain, Juan Carlos I, and a ghostly and nightmarish parade of various figures from the recent history of Spain, El Rey tries to take apart the conciliatory forgetful story of the Spanish Transition. The film, moreover, is put forward as a militant manifesto (which derives from the social movement generated in 15M), as the final objective is to put the film freely at the public’s disposal, that it should be a work of public domain under Creative Commons license. A document available to everyone, not made for profit, without ownership, in order to spread awareness and invite reflection.

El Rey and ROI SOLEIL overlap in their performative (and aristocratic) roots. The latter is directed by Albert Serra who, after La muerte de Luis XIV, elaborates a variation around this figure in a performance staged in the Galería Graça Brandão in Lisbon for seven days during which his regular, the non-professional actor Lluís Serrat, performed the death rattles, agony and final moments of the Sun King. With this material, with unusual lighting and reducing the palace to its minimum expression (in Serrat’s costume), Serra constructs this film in which the scenic becomes highly cinematic material thanks to the framing and the editing. The aristocracy in its grandeur and its stupidity, between the sublime and the grotesque, in a collision between the representation of power and the forces of art.

Finally, SANTOS #2, WORK IN PROGRESS, by Antón Corbal, places us in the utopian terrain of the creative and visionary process through the figure of the Galician filmmaker Oliver Laxe. By inviting us to enter via the film into the landscape of the surroundings in which Laxe lives and works, observing the dynamics, the film proposes a line-up with the mental state in which “magic happens”.

This is the group of feverish beings who build other worlds, here and now, our gang of endless revolutionaries. The Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran thus unwittingly found in his History and Utopia a defining key for our use and enjoyment that subverts the tormented burden of his thought to raise us up to the power of this violent desire for joy that this section predicts.