The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was an artist-led organisation, established to distribute and promote work that was considered too unconventional for the mainstream. One of the forerunners of a movement that led to film co-operatives being established all over the world, the LFMC was unique in combining three different activities within a single location – it had a workshop for producing new films, a distribution arm for promoting them, and its own cinema space for screenings. In this environment, Co-op members were freely able to explore the medium and control every stage of the process.

The LFMC was a direct development from a film society organised by

Bob Cobbing, an experimental poet who was then manager of the paperback department of one of central London’s leading alternative bookstores. Better Books, based just off Charing Cross Road, sold publications by City Lights and Grove Press, books by William Burroughs and other modern literature and esoterica,

and was a meeting point for underground culture. More than just a shop, it was

a social centre that played host to exhibitions, performances, poetry readings and film screenings, events which took place either on the shop floor or in its more spacious basement.

An inveterate organiser, Cobbing had established the Hendon Film Society in 1953 as one of a range of activities presented by his Hendon Arts Together group. On moving to the nearby borough of Finchley, film screenings were arranged

under the auspices of Cinema 61, later renamed Cinema 65 when Cobbing began to work at Better Books in January of that year. The audiences that gathered

at these events were aficionados of international art cinema whose interest in

the avant-garde was fostered at a time when it was difficult to see. Some of the members, such as the film critics Ray Durgnat and Philip Crick, would have been aware of contemporary developments in New York around Film Culture magazine, the New American Cinema Group and their driving force Jonas Mekas, and began to discuss the formation of a similar centre in London.

Mekas and his associates had founded the New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative in 1962 as a non-selective agency for independent and experimental films. Anyone could deposit his or her film in distribution, thereby becoming a member of the collective. All films were considered equal with none being actively promoted above another when they were made available for hire to film societies, colleges, cinemas and museums. A percentage of the rental fee was retained to cover the Co-op’s basic running costs and the larger share was paid directly to the filmmaker. The co-operative structure removed the need for commercial distribution and empowered the makers to remain in control of their work.

Following six months of meetings that began with a proposal to establish a branch of the New York Coop to circulate films in Europe, the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was formally inaugurated on 13 October 1966. Initial discussions

had taken place at both Better Books and Indica Books, but it was at the former that the LFMC was eventually based. Joining the core group of Cinema 65 regulars were two Americans that were now living in the UK – Stephen Dwoskin and Harvey Matusow.

[...]

One of the LFMC’s first public events was the ‘Spontaneous Festival of Underground Films’ at the Jeannetta Cochrane Theatre, a six-day fundraiser for its magazine Cinim. The Co-op then held regular programmes at Better Books for a year until the paperback department was closed by its new owners and Cobbing lost his job. The founding group continued to manage the Co-op from private addresses, organising screenings at other venues such as the ICA and the Arts Lab, a new space that had its official opening in the same month that the bookstore closed down.

Occupying a former factory at 182 Drury Lane, the Arts Lab was an idealistic, multi-disciplinary venue that would significantly impact on the Co-op’s development. Begun by Jim Haynes and Jack Henry Moore, it encompassed a theatre for experimental performances, a gallery, cinema and café. The roof of the basement cinema was so low that seating was relinquished in favour of a thick foam floor for lounging on. There were frequent all-night screenings, and films might be shown accidentally or intentionally with the reels in the wrong order. The wide end wall, used as the screen, invited expanded projection as two films could be shown there alongside each other.

For its fledgling years, the Co-op would be located firmly within the counterculture, between the experimental poetry circles and the psychedelic music scene. Films were often shown in lightshows at nightclubs like UFO and Middle Earth, projected while DJs played records or during early concerts by Pink Floyd and Soft Machine.

Independent of the activity at Better Books, a younger crowd of film enthusiasts gathered at the Arts Lab, where David Curtis’ cinema programme

grew to include screenings of classic avant-garde films, visiting experimental filmmakers (Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland, Gregory Markopoulos), Warhol films and independent features. When Malcolm Le Grice began to attend, along with his students from nearby Saint Martin’s School of Art, a new group that were interested in making, rather than just watching films, became an important presence.

As the Arts Lab filmmakers began to organise themselves it soon

became apparent that, for practical reasons, they should unite with the Co-op.

The younger participants emerged as the more dynamic group and during the next year, LFMC founding members Cobbing, Crick, Durgnat, Latham and Paul Francis all resigned. (Stephen Dwoskin and Simon Hartog withdrew in 1969.) With the direction of the Co-op now being steered by Curtis and Le Grice, the focus became very much on production.

Le Grice had begun filmmaking in 1965. A visual artist making large construction paintings influenced by Rauschenberg and Cage, he was keen to introduce the element of time into his work but was then unaware of the avant-garde film movement. Collecting discarded footage from the dustbins outside

the film labs in Soho, Le Grice assembled his first 16mm film Castle 1, a primitive piece of English expanded cinema. Also known as “The Light Bulb Film”, its unusual technical requirement was for a bright light bulb to be hung in front of the screen and intermittently flashed on and off. In the moments when the light bulb was turned on, it not only bleached out the projected image but also illuminated the audience, pulling them out of the film illusion and back into reality. When Le Grice showed Castle 1 to David Curtis at the Arts Lab, Curtis responded by screening films by Bruce Conner and others, demonstrating a context for such work and encouraging Le Grice to continue. Having fabricated a film printer (using an

old projector) and a continuous processor (drainpipes and a hairdryer) in his garage at home, Le Grice used this equipment to create all of his early works. He was to become a central figure in organising the Co-op, building and running the workshop, and a major writer, teacher and theorist. Many of the younger LFMC filmmakers that rose to prominence in the 1970s, including Gill Eatherley, Annabel Nicolson and William Raban, were his students.

David Curtis and several colleagues split from the Arts Lab in November 1968 following disagreements over management. Their plans of starting a similar project took almost a year to come to fruition but in late 1969, the New Arts Lab, more formally known as IRAT, the Institute for Research in Art and Technology,

was opened. The LFMC moved in to share the space with other initiatives including a cinema, art gallery, and printing, video and cybernetic workshops.

It was at IRAT that the LFMC uniquely established a distribution o ice, film workshop and cinema programme within the same building. The ability to produce, promote and project films under one roof established a creative loop whereby the screening of each new work would in turn influence and engender the production of the next. There was a tight dialogue between the different filmmakers who

each had their own distinctive styles but were united in the task of maintaining

the Co-op. Though they would debate ideas and assist each other with technical matters, each film was usually the product of a single author. Those that could operate the laboratory equipment would either demonstrate it to enable others, or print and process films for them.

Camden Council provided the IRAT building on Robert Street, close to Euston Station, on a short-term let before its impending demolition. Over the course of the next decade the Co-op moved three more times to similar locations: empty factories, dairies and laundries. Its last permanent home (from 1978 to 1995) was a building owned by British Rail on Gloucester Avenue in Camden Town. Each of these spaces housed the LFMC’s three core elements of distribution, workshop and cinema.

[...]

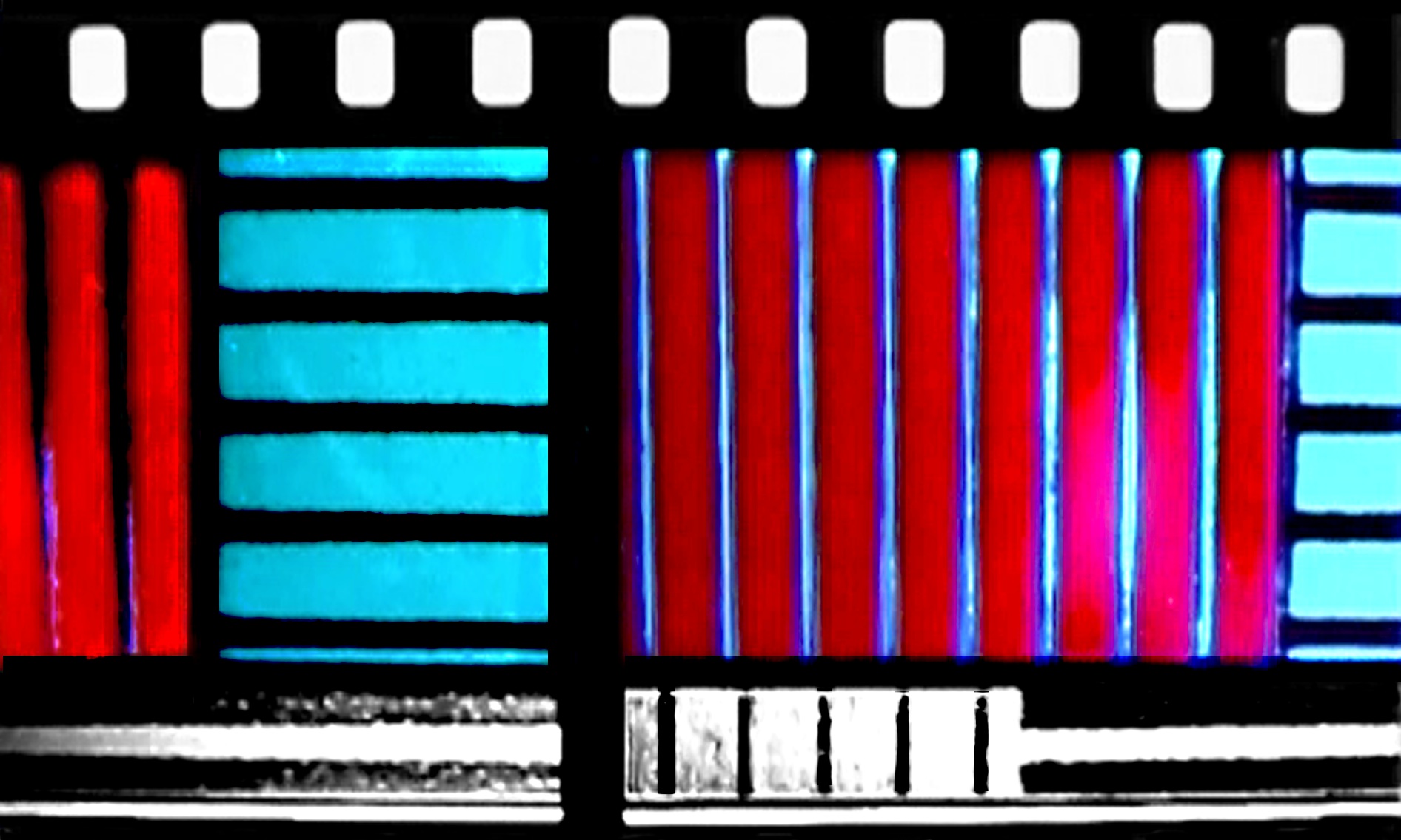

Many of the Co-op’s filmmakers had backgrounds in fine art rather than cinema. Malcolm Le Grice, his students and their contemporaries (such as those studying at Chelsea with Anne Rees-Mogg and at North East London Polytechnic with Guy Sherwin) gravitated towards film because it was a sculptural medium with the properties most suited to the phenomena they wanted to explore. Work made at the LFMC shared some traits with American ‘structural film’, characterised by its emphasis on the relationship between the physical film strip, its immaterial projected image and the effect it has on the viewer, but looked very different. The British films were more sensual: the physical film material is always right there, visibly present at the same time as the image. No longer just the carrier, but an equal part of the content.

Peter Gidal described the British and European work as ‘structural/ materialist’, both highlighting the physical nature of the films and alluding to Marxist politics. In his “Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film”, practically a manifesto for the core group of LFMC filmmakers in the early 1970s, Gidal wrote that, “Each film is a record (not a representation and not a reproduction) of its own making” and that it “asserts its real duration and coming into presence through the mental activation of the viewer.”

The harsh conditions of the LFMC’s environment certainly contributed

to the creation of what was often regarded as ‘difficult’ work, but it was the workshop that consistently gave the London films their distinctive look. In the Co-op workshop, the physical production, the printing and processing of a film was an integral part of its make-up. The laboratory became a fundamental tool of the artistic process, as vital to the filmmakers as the camera in conventional cinema. It was now possible to pull strips of film (or any other material) manually through the printer, to play with exposure levels, introduce light leaks and foreign objects, to set up loops, or superimpositions and apply filters and mattes. Images could be degraded through generations of duplication; chemicals could be manipulated to alter the composition of the emulsion.

Many works were process based, with ideas being followed through with no concern for a tidy presentation of the final result. The film strip was no longer used simply to impart narratives, transmit information or convey simple emotions. Works questioned the passive role of the spectator and the authoritarian status of the filmmaker, making the viewer an active participant in the experience of films that demanded to be engaged with. Films were being made in conscious opposition to the ‘dominant’ cinema, where laboratory processes were usually concealed, and by democratising the methods of production the filmmakers bypassed the commercial laboratories and their implied connection to the film industry.

The filmmakers were also reacting against the illusionistic structuring of ‘real time’ in narrative cinema and bringing the production of a film back to a 1:1 relationship with the viewing experience. Durational concerns were fundamental

to much of this work, propelled by the influence of Warhol and Snow. Le Grice regarded duration as a concrete dimension, as real as the spatial dimensions of a piece of sculpture. Both Le Grice and Gidal considered their films as problematic work that raised issues rather than illustrating theories. Theory came after practice, and the British were driven to write so much criticism on their work because no one else was doing so.

[...]

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative survived until it was finally dissolved in 1999, having merged with London Electronic Arts (previously London Video Arts) to create the Lux Centre for Film, Video and Digital Arts. Following the Lux Centre’s sudden closure in 2001, LUX was established to distribute the former LFMC and LEA collections, promoting historical work alongside that of younger artists, and including advocacy, education, publishing and exhibition amongst its activities.

The Shoot Shoot Shoot touring exhibition that began in 2002 stimulated

a new wave of interest in Co-op filmmakers, who have since seen their work presented internationally within both art and film contexts, and reassessed in print. As more information about this period comes to light, it’s crucially important that the films are preserved and projected on their original formats so that the creative achievements of this group and the example set by the co-operative nature of

their enterprise can continue to inspire. It now seems extraordinary that such a small organisation provided the environment in which so much vital, engaging

and historically significant work could develop.

By Mark Webber

Extract from the text originally published in Shoot Shoot Shoot: The First Decade of the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative 1966-76, edited by Mark Webber, published by LUX, 2016. www.lux.org.uk